Each day at Vidant Health, incredible nurses go above and beyond to care for the patients and families of eastern North Carolina.

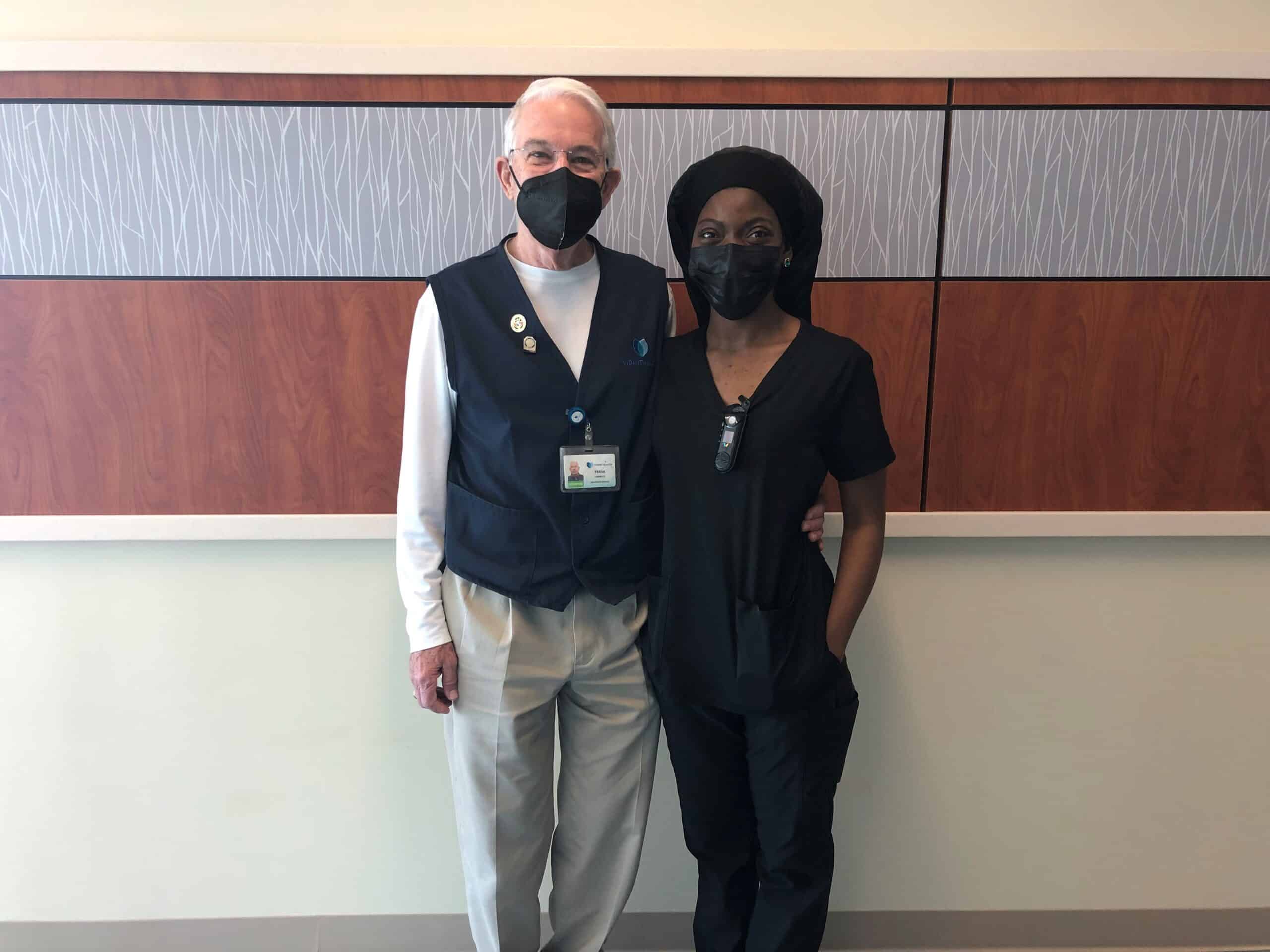

In February, ECU Health Medical Center (VMC) volunteer Frank Crawley had a moving experience with nurse Felicia Parker at ECU Health Cancer Care that he felt compelled to write about.

“What you don’t know is you did something to me that day,” Crawley said to Parker, as the two met again exactly a month after their interaction. “You moved me to do some things that I’ve wanted to do for a long time. That’s to write about some things having to do with this hospital and how much it has meant to me.”

This National Health Care Volunteers week, we are proud to share the below story written by Crawley after his experience at VMC.

“On the morning of Feb. 15, 2022, a call came to Patient Escort to bring a wheelchair to the Cancer Center, room 418, to transport a patient to the Dental Clinic. I took the call. When I arrived, I knocked on the door, opened it, greeted the occupants and announced that I was there to take the patient to the Dental Clinic. Lying in the bed was a frail, elderly man. Standing by his side was his wife, who immediately said there was no way her husband was able to make the trip to the clinic in a wheelchair.

I left the room and located the nurse assigned to room 418, whom I later learned was Felicia Parker. She and I both entered the room. Ms. Parker explained to the patient’s wife that her husband desperately needed dental work. The wife seemed very concerned that her husband lacked the strength to make the trip, that his blood pressure would drop and that he could have a seizure, particularly if taken in a wheelchair. She said that he might be able to make the trip in his bed. The soft-spoken Ms. Parker explained that the bed was too large to transport into the clinic. Additionally, she said that to alleviate the wife’s concerns, she would accompany her husband to the clinic, assuring her that every precaution would be taken. First, she explained that we would exchange the Staxi for a Stryker wheelchair, carry an oxygen tank with us, along with a blood pressure/heart rate attachment to monitor her husband’s vital signs.

The wife began to weep quietly. She walked into the bathroom and continued to sob, fearing for the welfare of her husband. Ms. Parker followed her to the bathroom. She spoke softly, lovingly to the patient’s wife, hugged, consoled and reassured her that we would take every precaution to see that her husband made the trip to the clinic without incident. Still hugging, Ms. Parker told the patient’s wife that she would call her once we reached the clinic. I was so impressed at that moment with the love, patience, caring and empathy Ms. Parker showed her — far beyond what I had expected to witness that day. With the wife comforted and reassured, Ms. Parker and I located a Stryker chair, added an oxygen tank and a vitals’ monitor. Next, Ms. Parker said that she was raising the bed to a sitting position so that the patient could sit upright for a few minutes and adjust to the change in position. Doing so, she explained, we would be able to see whether his blood pressure and heart rate would respond favorably to the positional change. Next, Ms. Parker and I moved the Stryker chair next to the bed and slowly moved the gentleman’s feet off the side of the bed. All went well — at first.

Within seconds of moving his feet off the bed, there was a sudden drop in the patient’s blood pressure and a change in heart rate. Carefully but quickly, Ms. Parker moved the patient’s feet back onto the bed and slowly lowered the bed. She immediately left the room and called for backup help — not calling for a “code blue” but the next level below, as I heard her say. Within a few minutes, the room was filled with attending physicians, nurses and aides. I quickly moved back, stepping out of the room to allow Ms. Parker and the medical staff space to work. Within what seemed like only a few minutes, the patient’s vital signs were restored to normal, and the room was calm again. Ms. Parker then turned to the patient’s wife, hugged and comforted her.

With the room restored to calm and the father’s vitals stable, Ms. Parker came to me and thanked me for my help.

“No,” I said. “Thank you for allowing me the privilege to witness, firsthand, nursing at its very best.”

Not only was Ms. Parker highly competent, as evidenced by the technical skills she displayed, she also possessed that rare ability to sincerely comfort, console and empathetically connect with the very distressed patient’s wife. Empathy is near impossible to teach. Neither can it be faked. Deeply moved and with tears in my eyes, I hugged Ms. Parker.

“Never had I expected to report to volunteer duty Tuesday morning and see the loving, compassionate face of Jesus on display,” I said.

That day was most rare and wonderful, and I knew it.

After writing down his experience, Crawley shared this with the volunteer team and eventually it found its way to Parker. When she received the email, she had her daughter read the story to her sons. Parker said she was moved by him sharing his experience with her and her family.

“It’s nothing that I gave a second thought to – it’s just what we do every day,” Parker said, who will celebrate three years in the system in June. “Sometimes we kind of don’t look at what we do, how it impacts others. Especially, we feel like it’s just something that we’re just supposed to do. You’re supposed to get up, you’re supposed to greet people when we see them. We don’t think anything of it. That’s what it was for me. It was just, ‘Hey, what you do does matter.’”

Crawley said he has been volunteering at the medical center for nine years. Previously, he was an education professor at East Carolina University.

“In the busyness of life, and I think it has a lot to do with my age, I look for those moments that I can connect with people or when I can see them connecting, because I believe that’s what we were born to do,” Crawley said.

“We do a lot of things for which we get paid and it’s difficult to find something in you down deep that in that busyness,” Crawley said. Then looking at Parker, he continued, “I know you had lots of other patients, but in that busyness to console the woman who wasn’t your patient. You saw something there that was a greater need and you met that need. That was just powerful.”

We are so proud to have experiences like this unfold along the halls of Vidant hospitals each day. Thank you to the care teams, volunteers and team members who serve eastern North Carolina. If you are interested in joining the Vidant team, visit our Careers site.

Regardless of the world around us, cancer does not pause for anything. Colorectal cancer screenings have severely decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and doctors are worried this will lead to more cases of advanced stages of colorectal cancer.

In general, colorectal cancer starts as an overgrowth of the tissue in the colon, called a polyp. There are different types of polyps, some of which change into cancers in the future.

“We want to find out about colorectal cancer before there are any signs or symptoms,” said Dr. Warqaa Akram, colorectal cancer surgeon for ECU and Vidant Health. “We want to catch it when a person is healthy because colorectal cancer is very treatable when caught early. Some polyps are small and won’t give you many symptoms, if at all, when it starts.”

Providers aim to find polyps and remove them before they progress into cancer. More advanced tumors can cause bleeding and obstructions. That’s why doctors are recommending screenings five years earlier, at age 45. However, that age may be lower for those who are high-risk, meaning they have a close relative such as a parent or sibling who has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

“If you have a family history of cancer, we begin screenings at age 40 or 10 years before the diagnosis of a family member, whichever comes first,” said Dr. Akram. “For example, if the father was diagnosed at age 45 with colorectal cancer, children should begin screenings at age 35. If a father was diagnosed at age 60, children should begin screenings at age 40.”

Overall, the instance of colorectal cancer is decreasing, likely due in part to screenings. However, the incidence of colorectal cancer in younger people is on the rise. Although the reasons are not completely known, an increase of processed foods, poor diet and lack of exercise are all contributing factors. While the causes of colorectal cancer are unknown, and some are unmodifiable like genetics, some of the largest contributing factors are eating a diet high in processed foods and red meat. Experts encourage a high-fiber diet to help prevent cancerous polyps.

It is important to note that colorectal cancer disproportionately affects Black Americans more than any other race in the country. In eastern North Carolina, the incidence of cancer is 20 percent higher in African Americans than any other race, and the risk of death is higher by about 40 percent. Socioeconomic status and lack of access to health care are some of the reasons incidences in colorectal cancer are higher in the African American population.

“Knowing that younger people and the African American population are having higher incidences of colorectal cancer, it is very important to get regular screenings,” said Dr. Akram. “We know a lot about colorectal cancer, and it is a type of cancer we know how to treat and we know how to defeat. The earlier we catch colorectal cancer, the better the results and possibility of being cured.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, colonoscopies decreased by 90 percent at Vidant Health.

“This is very alarming because incidences of more advanced colorectal cancer could be in our future in eastern North Carolina,” said Dr. Akram. “We are learning about less incidences of cancer and risking that people will present with more advanced stages of cancer.”

“I know no one wants to hear a cancer diagnosis, but thanks to early detection through screenings, colorectal is mostly preventable, treatable and often curable,” said Dr. Akram. “Colorectal cancer does not have to be a death sentence.”

For more information about the risks, prevention and screening resources for colorectal cancer, or if you do not have a primary care provider, please contact the Prevention Clinic at ECU Health Cancer Care at (252) 816-7475.