“I was just doing what is right.”

Sheila Grady, Community Liaison with ECU Health’s Home Health and Hospice, has never been one to seek the limelight in her 29-year career. In fact, she’d rather be behind the scenes, helping people and making a difference.

“She has a heart of gold, and she’s going to do whatever it takes to assist and serve our patients and families,” said Sarah Taylor, Sheila’s supervisor and the manager of marketing and hospice volunteer coordinator. “She understands we are a business, but we’re in a people-serving business and that’s our number one goal.”

When Aaron Hair contacted Sheila about having two memory bears made after the death of his father, her drive to do what’s right while serving patients and their families got people’s attention.

“My dad was diagnosed with cancer two years ago,” explained Aaron. “When the decision was made that he would stop treatment, he was admitted to palliative care at the Medical Center, but his doctor and nurses recommended the hospice house in Greenville.”

While his father was in the hospice house for less than 24 hours before passing away, Aaron recognized the hospice team members made a difficult situation easier to bear.

“They made us feel at ease and explained everything,” Aaron said. “From the facility to the staff, they were all top notch.”

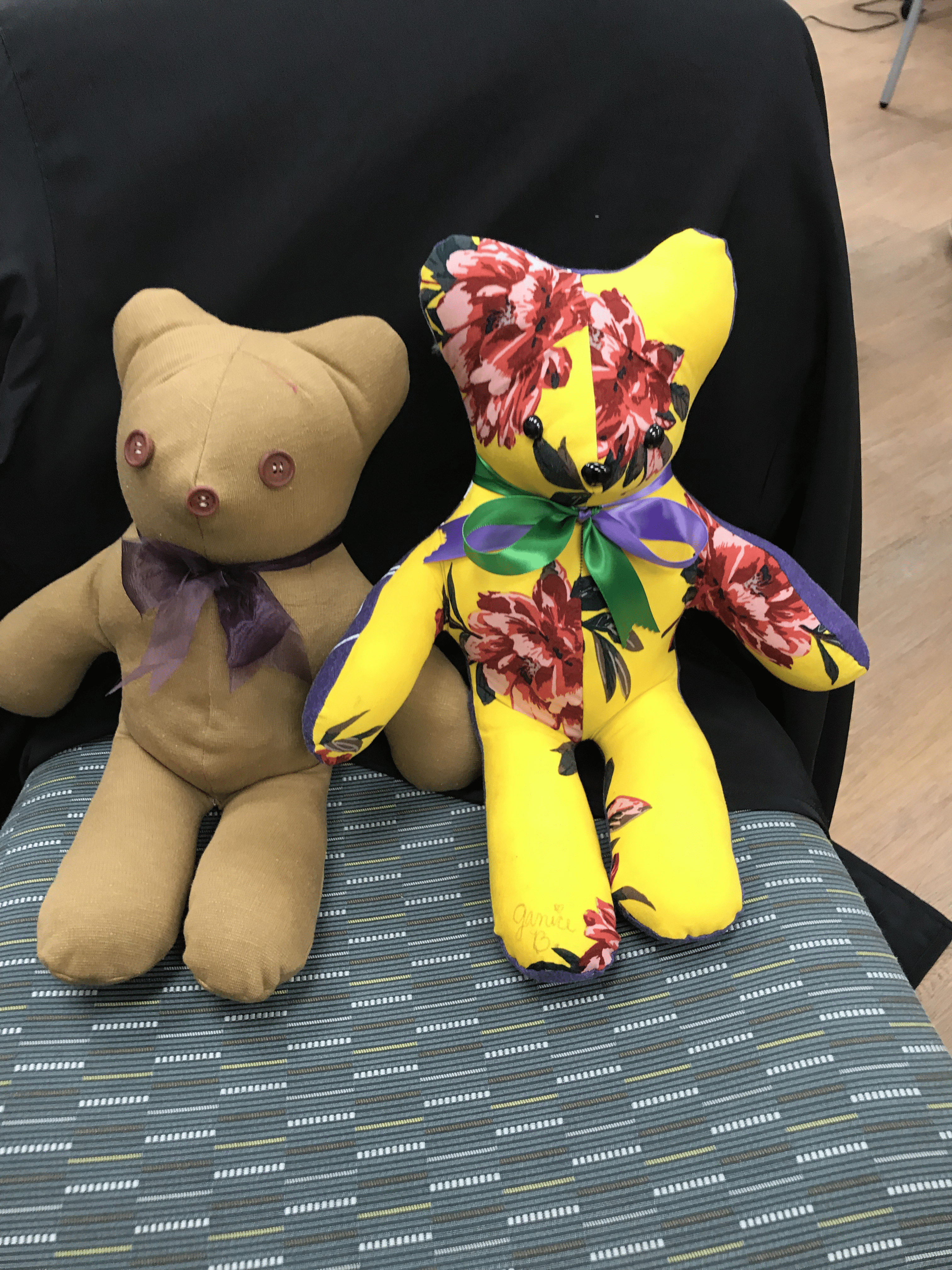

After his father’s death, Aaron and his family wanted to make use of the Memory Bear program, a service of ECU Health’s Home Health and Hospice team that makes teddy bears or pillows using an article of clothing from the family member who passed away. Sheila has run the program for the past two years.

Sarah noted that it was Sheila’s leadership that made the Memory Bear program what it is today.

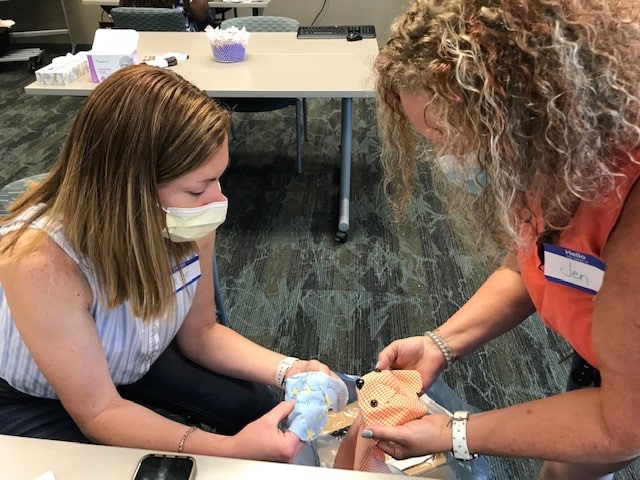

“Now we have workshops in Greenville and Kenansville, and we’re serving all hospice patients on our service. And there’s a lot of love put into these bears,” Taylor said.

The work, Sheila emphasized, is done entirely by volunteers.

“These are nurses who pick up materials and drop off bears after their shifts,” Grady said. “Some are retired from health care, and some are retired teachers. They come from all walks of life, and they don’t ask for a dime.”

Aaron contacted Sheila directly to request two memory bears, one for each of his daughters. The challenge, however, became how to get his dad’s shirts to the seamstresses.

“I live in Johnston County but was working in Havelock. It would have been challenging to get the shirts to Greenville,” Aaron explained. As they talked, Sheila learned that his commute took him right by her office in Duplin County. “She gave me her personal cell phone number, and I called her when I was on the way so we could plan a meet-up. She didn’t have to do that.”

As for Sheila, it was just an example of her drive to do the right thing.

“He was a young man who lost his father,” she said. “He was an only child, and he was asking for something for his family.”

Once she got the shirts, Sheila realized that Aaron had only asked for bears for his daughters, but nothing for his mother.

“She called me and said, ‘You didn’t mention making anything for your mom,’” Aaron said. “But I only asked for two bears because that’s the limit set on the brochure, and I wasn’t going to ask for more than that.”

Sheila, however, emphasized that the two-bear limit is a flexible parameter. ”We listen to the person’s story and we make what is right for each person. I knew we needed to make a pillow for his mom.”

A few days later, the seamstress working on the project contacted Sheila with another observation.

“She said, ‘This man didn’t ask for a thing for himself,’ and she told me they had enough material to make a pillow for Aaron, as well,” she said. “So that’s what they did.”

When it came time to deliver the items, Sheila again went out of her way to ensure they were delivered prior to a planned trip out of town. When she brought the items out, Aaron learned that not only had the bears and pillow for his daughters and mom been created, but that a pillow had been made for him as well — made from the shirt his dad wore the last time the two of them went fishing together.

“I hadn’t thought about myself,” Aaron admitted. “It was heartwarming for someone to think about that.”

Sheila confirmed that it was common for family members not to think of requesting a pillow or bear for themselves, even when it’s someone familiar with the program.

“One of the nurses who hired me for this job – her husband died suddenly. I reached out to her and told her, ‘I want to make a bear for you,’ and the nurse said she had never even thought about it. We made her a bear, and later she sent us a picture of her in bed with the bear made from her husband’s pajamas,” Grady said. “Below the picture she wrote, ‘I still have him with me.’ That’s what the Memory Bear program is all about.”

After his meeting with Sheila, Aaron knew what he wanted to do.

“When I left the parking lot that day, I went home and called my brother-in-law, who works for ECU Health, to get Mrs. Grady’s supervisor’s name so I could let them know what she had done,” Aaron said. “Mrs. Grady is a loving and caring lady who I feel I have known my whole life.” He ended up writing an email that garnered a lot of attention.

“I had no idea he would write that email,” Sheila said. “I don’t do this for the recognition.” She was recognized, however, at a surprise gathering in her Kenansville office on Oct. 9. “I was shocked, and it’s difficult to surprise me,” Sheila laughed. “When I saw my husband and family in my office that day, I knew something was up.”

However, she is quick to pass credit to others.

“The team makes this happen,” Sheila said. “The nurses, PTs, aides, OTs and social workers. The chaplains. The seamstresses who make the bears. They’re the real heroes.”

That her home office in Kenansville has won multiple Patient Choice Awards this year bears that statement to be true.

Sheila also emphasized that the ECU Health hospice service, which is made unique by the Memory Bear program, is deeply important.

“I wasn’t sure I’d like the hospice setting when I was first hired,” she admitted. “But I want to make a difference in people’s lives, and that’s what we do. Now I educate people about our home health and hospice services and assist with referrals, and I love it because I know I am making a difference.”

Her supervisor, Sarah, agreed: “We can walk the journey with these patients and their families, and Sheila is the type of person who is going to make sure the family is OK and she can bring them some peace.” Sarah also noted that the Memory Bear program has gained a positive reputation in the community: “Now we have people say, ‘Oh, you’re the hospice with the memory bears?’ and that’s awesome.”

Sheila has plans to retire in mid-November, although she’s not retiring from the Memory Bear program just yet.

“I have another grandchild on the way, so I’ll be spending time with my family, but I come from a long line of people who believe work is a good thing,” Grady said. “I’ll volunteer with the Memory Bear program for sure.”