It’s not just in October, which serves as Breast Cancer Awareness Month, that you can find the ECU Health Cancer Care Outreach team making connections in the community.

Jennifer Lewis, outreach coordinator for cancer care at ECU Health Medical Center, said she spends much of her time reaching out to community partners, talking to groups in Pitt County and beyond, and connecting with ECU Health patients and families. However, she said, the most rewarding part of her job is the monthly free breast clinic she helps run.

The clinic, for women in Pitt County age 40 and older who are low income and do not have health insurance, provides screening mammograms while sharing other resources available for health care in the area with those participating in the screening.

Lewis said she is grateful to help with the program and is proud of the impact it has on Pitt County.

“Patients don’t see a bill because of donations to the Cancer Center and the ECU Health Foundation, and that’s just an amazing thing we get to offer,” Lewis said. “We start with a breast exam by a provider to check for obvious abnormalities. Then they have their 3D mammogram, so they get state of the art imaging just like anyone else would get and they don’t get lesser quality. If they have an area that is of suspicion, we can do a diagnostic mammogram and if the radiologist looks at those images and feels like there’s some more concern about something, next would be an ultrasound of that area of suspicion. The program that we have here pays for all that.”

She shared that while ECU Health Beaufort Hospital and Outer Banks Health currently have their own programs outside of Greenville and Pitt County, other hospitals across ECU Health’s system are working toward establishing the program as well.

Lewis said the partnerships and volunteerism associated with the program make it truly special. She and her team work closely with the Pitt County Health Department to help patients who need further care through the Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program (BCCCP).

“We can’t do this without our partners, that’s for sure,” Lewis said. “We have such a great working relationship with the Pitt County Health Department and the mammography technicians, Patient Access Services, Language Access, Volunteer Services, radiology and ultrasound, and then our nurse residents who help out all work together so well. After patients are seen during the free clinic day, we have Access East on hand, too, to share information and resources about other services they can get access to. It’s such great teamwork all around that makes these events successful.”

The program sees so many patients throughout the year that they’ve recently added an extra clinic day twice a year, once in February and once in October, to help meet the needs of the community.

While Lewis is frequently in the community talking to groups and spreading awareness, October is especially important. She said she’ll spend much of the month meeting with community groups and in churches discussing risk factors, signs and symptoms and why screenings are important.

“This month is an intentional time set aside to speak about risk factors, family history, and signs and symptoms, because that’s the one time of the year that you can sit back and think, ‘OK, am I having any of these symptoms?’ Or ‘What is my family history? Because last year I didn’t have any, but this year my mother or sister has been diagnosed with it.’ It really creates that intention for people to have that moment sometime during the month,” Lewis said. “Whether it’s an ad on Facebook or hearing someone like me speak, it’s important to have that moment of reflection, remind yourself to get a mammogram and just put that in the forefront of women’s minds.”

She said if there’s one thing she could remind the community, it’s that anyone can be diagnosed with breast cancer. She noted that there are many myths, including that because someone is without family history, is otherwise healthy or is a male, that they cannot develop breast cancer. This is why she said it’s critical for everyone to be aware of signs and symptoms and receive screenings as recommended.

Resources

Breast Screening Events

ECU Health Cancer Care

More Breast Cancer Information

By ECU News Services and ECU Health News

Getting through medical school can be tough – long hours, books and tests, and more books. However, in between classes and all-nighters, two students from the Brody School of Medicine have established a flourishing volunteer program to bring doula-like services to a region of North Carolina starved for birthing support.

The birthing companion program was started in October 2022 by Uma Gaddamanugu and Shantell McLaggan, both second-year Brody students and Schweitzer fellows. The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship supports graduate health professionals drawn from across the state who learn and work to address unmet health care needs in North Carolina.

Gaddamanugu’s and McLaggan’s fellowship project is focused on improving birth experiences of high-risk pregnant mothers in eastern North Carolina through the free birth support program to add an extra layer of support for women in the birthing process.

Patient populations in rural parts of eastern North Carolina simply need more help, Winston-Salem native Gaddamanugu said, from prenatal care through the laboring process, and certified doulas are an expensive out-of-pocket resource for which most North Carolinians must pay out of pocket because health insurance often doesn’t cover the cost.

“We are the only hospital with a high-risk labor and delivery unit for half the state. You think about how far some of these people have to travel, which makes it way harder for their support people to come with them,” Gaddamanugu said.

In February 2022, the North Carolina Institute of Medicine reported that the state’s maternal mortality rate was 27.6 per 100,000 births, which is slightly lower than the national average, but more than double the previous year’s rate of 12.1 per 100,000 births.

A 2021 study by the North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Committee reported that 60 women died from pregnancy related causes from 2014-2016. Of those, nearly 60% were from minority racial categories and more than one in three were from rural areas. What’s more troubling – the study determined that 70% of maternal deaths could have been prevented by changing “patient, family, provider, facility, system and/or community factors.”

The program

At first, the program had 18 volunteers, but since its inception in October 2022 the ranks of birthing support volunteers have doubled to 37. At the beginning of February, the volunteers had assisted with more than 70 births, which is “way past our goal that we had initially set,” Gaddamanugu said.

Volunteers from the program come from a wide range of backgrounds, though most are medical or nursing students. Some are undergraduate students from main campus who want to be part of a program that serves the community. For now, the program is staffed almost completely by ECU students, though Gaddamanugu and McLaggan will soon hand the program’s day-to-day management off to first-year medical students who aim to open the program up to the public.

“Our program is very much modeled off a program at UNC. They’ve been doing that for about 20 years,” Gaddamanugu said. “A Wake Forest medical student started a similar volunteer doula program two years ago through the Schwitzer Fellowship. It’s just neat to see that it was possible with the structure of the organization to bring that program here, because there’s a whole different need in eastern North Carolina.”

Gaddamanugu stressed that the volunteers in the program, who support the labor and delivery services at ECU Health, aren’t certified doulas but rather are there to help during the immediate labor process. For one delivery, that might be a non-clinical, non-medical role – a friendly face and a hand to hold – and in other cases it might be running through the hospital to find a phone charging cable so a mother can stay in contact with her other children at home.

Leslie Coggins, a charge nurse on the labor and delivery unit at ECU Health Medical Center in Greenville, said the volunteer program has been a great success, both for the mothers in the delivery process as well as for students on track to become the next generation of health care providers.

“We’ve always had a great relationship with our residents, but now we have almost a pipeline — doctors, potential doctors, nurses, someone interested in birth and supporting birth in its natural function,” Coggins said. “To share that experience with up-and-coming providers and nurses who will be taking our places someday is huge.”

While the volunteer program is currently staffed by students, the student organizers and Coggins as the nurse manager of the labor and delivery unit hope to soon include members of the public. Those interested in volunteering should contact the program by emailing [email protected].

Training medical professionals

The ECU version of a volunteer birth companion program is rooted in experiences both medical students had working as volunteers in hospitals in doula-like roles. Gaddamanugu volunteered during her time as an undergraduate at UNC; McLaggan, who is from Thomasville, spent several years after her undergraduate education working at the Cherokee Indian Hospital in western North Carolina and helped establish a volunteer doula program there.

Both students are interested in pursuing a career in obstetrics.

McLaggan’s mother told her from an early age that she was smart enough to be a doctor. After researching the requirements and being captivated by the science of medicine, she fell in love with the idea.

“I feel like I have the mental, emotional and the physical capacity to do something as strenuous as being a doctor,” McLaggan said. “Because I have those qualities, I feel like it’s my obligation to become a doctor and serve people to the maximum of my abilities.”

Medicine was also a calling for Gaddamanugu, who said that the challenge is humbling but she sees a future where she can make a difference by “maternal and child health disparities in our community” which fit the impact that she hopes to make in the world.

She said that the experiences at the bedside have colored the conversations that she has with her medical school peers about the experience of medicine from the patient’s perspective.

“We know birth is hard, but here is what it really can look like,” Gaddamanugu said. “The U.S. has an awful maternal mortality crisis, and we can hear those numbers all day long in school, but the numbers don’t mean anything until you see it in person, and you realize some of these patients are extremely sick.”

For Dr. Kerianne Crockett, ECU Health OB/GYN and Brody clinical assistant professor, the program has clear benefits for the patients she serves. She has heard from patients who appreciated having another source of support during their delivery.

“Delivering a baby is one of the most exhausting, exhilarating, sometimes scary experiences of a patient’s life,” Crockett said. “There is good evidence that patients with a continuous support person present throughout labor — whether that person is a family member, a spouse or a doula — have better birth outcomes, including lower rates of cesarean delivery. I am so proud that our bright, compassionate, empathetic medical students are now able to be that continuous support person for all kinds of patients, including those who otherwise would not have had anyone besides the medical team there for their delivery.”

Student involvement in health care delivery, and the unique perspectives students offer patients, is a hallmark of a large academic health system like ECU Health. As students learn from the clinical experience of providers at ECU Health, they are empowered to innovate and bring ideas to the table that lead to better patient experiences and brighter outcomes.

“As an academic health system, our medical students help to enrich the patient experience with their energy and ideas,” said Angela Still, senior administrator of women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center. “The birthing support volunteer initiative is a great example of how Brody students go beyond the walls of the classroom and make a direct impact on the patients we’re proud to serve.”

Serving eastern North Carolina

Sometimes the most important support that a birthing companion can provide comes from skills that can’t be taught in a formal doula class.

McLaggan remembers one time she volunteered with a woman who had a number of kids already — the most recent born by C-section. The medical staff recommended another C-section, which the woman was reluctant to agree to due to the complications she had with the previous birth. The challenge that McLaggan was able to help resolve wasn’t convincing the woman to have a C-section, but rather just communicating with her at all. The woman was Haitian and spoke Haitian Creole and little English.

“I happened to speak French, which is very similar to Haitian Creole, so she was able to communicate to me, where she was coming from and what her needs were,” McLaggan remembered. “I was able to bridge that gap and she ended up delivering naturally. I felt so honored and privileged to have been in the room.”

Another of the volunteers in the program has similar experiences with language gaps being a hindrance to quality health care. An undergraduate student recounted to Gaddamanugu how, growing up in eastern North Carolina, she was always saddled with translating for her mother and siblings during medical appointments — a task that shouldn’t really be shouldered by a young person. The student volunteer said, though tears, that she was so grateful to be able to translate for delivering mothers because she knew first-hand the constricting fear and anxiety of being language-locked in a stressful medical situation.

While the language capabilities that some students bring to the hospital bedside are important, Coggins said, patient populations in eastern North Carolina are getting sicker, which often requires the health care team members to devote their attention to the physiological status of the patient.

“We try to promote natural delivery as much as we can,” Coggins said, but sometimes the medical conditions of the mother and baby require doctors and nurses to focus on the immediate illness. “One-on-one support is essential with our patients. A lot of times our sick population are not from around here and don’t have the support system in place, so this is an added benefit so our nurses can focus on what is medically happening and where we need intervene.”

Gaddamaugu is awed at the privilege of being present at a birth.

“I’ve cried every single time; it’s one or two single tears, but they were C-section babies and you could sense the relief in the OR the moment the baby comes out safe and healthy,” Gaddamaugu said.

McLaggan has known that being in the room during the birthing process is what she has wanted to do since before kindergarten. She’s seen a handful of births as a volunteer and continues to be amazed by each one.

“Words don’t describe how amazing childbirth really is. I get so overwhelmed with emotion when I see 37 to 40 weeks of work and love going into this child that is coming into the world,” McLaggan said.

Resources

The third Thursday of November is National Rural Health Day and ECU Health and the Brody School of Medicine are celebrating team members, faculty, staff and students by shining a light on the work they do to make a positive difference in the lives of the 1.4 million people living in eastern North Carolina.

A note from ECU Health CEO and Brody Dean Dr. Michael Waldrum: National Rural Health Day is a day to shine a light on the contributions of rural health professionals across the country. We created ECU Health earlier this year with high-quality rural health care in mind. The team members who work here truly personify the region and we wanted our name and logo to reflect that. We wanted our patients to know that the care we provide is backed by the educational excellence taking place at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University. More than anything else, we wanted eastern North Carolina to know that ECU Health will always represent them. That’s a testament to the more than 13,500 ECU Health and Brody team members, who embody our mission and serve our communities. Thank you for your service and commitment to our organization, region and patients.

ECU Health serves a vast rural region made up of 29 counties and home to more than 1.4 million people. Like many rural regions, people across eastern North Carolina face a number of systemic socioeconomic challenges which have negative impacts on health outcomes. Perhaps most tragic of all, the region has wrestled for years with higher infant death rates than the state average, driven by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, barriers in access to care and fewer local resources to support expecting mothers.

Dr. Madhu Parmar, an OB-GYN for ECU Health, practices in Ahoskie. She helps facilitate countless healthy deliveries, but the ones that don’t go as planned stick with her the most. That is because many of the complications are preventable, and adequate access to perinatal care helps facilitate positive outcomes for both mother and baby. The unfortunate reality is that rural and underserved communities simply lack access to the perinatal care they need.

“This issue is very personal because I feel like there are not enough resources, people and attention placed on caring for mothers and babies in rural areas,” Dr. Parmar said. “I feel like rural mothers and babies are the ones that need care the most and we must do all we can to ensure they have access to that care. You hear about smaller hospitals closing down their OB units and that just increases the risk to mother and baby. If a community has access to these services, you see how the mother and the baby can thrive. That’s what we’re aiming for at ECU Health, access for all.”

Dr. Parmar says the primary challenges she sees in her patients stem from poverty. Data tells us that 1 in 4 mothers in eastern North Carolina live below the poverty line and 1 in 8 are uninsured.

“Because of poverty, patients are not as healthy,” she said. “Obesity and chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, are the things presenting difficult challenges for normal patients, and those conditions are even more challenging for pregnant patients. The reality is that we take care of a lot of high-risk patients in the East because many of our patients experience poverty.”

Across the region, more than 50 percent of the mothers delivering babies at ECU Health hospitals are clinically overweight. In Ahoskie, where Dr. Parmar practices, the average Body Mass Index (BMI) is about 40, nearly 15 points higher than the high range of a healthy person.

Keeping patients informed and educated about their health has been a key focus, Dr. Parmar said. Understanding illnesses and what to watch for is half the battle; a healthy mom often times leads to a healthier pregnancy.

“A nurse who specializes in diabetes care comes to our office once a week to educate our patients,” Dr. Parmar said. “She teaches them how to monitor their blood sugar and how to improve their diet so that we have optimal outcomes for the babies. She works with our nurses, too, and makes sure they’re looking through patients’ blood sugar diaries when they come in. The biggest thing we can do is be available to these patients.”

Women’s care close to home

At a time when many rural communities across the United States are losing access to obstetrics and women’s care services, ECU Health is doing its part to maintain and enhance obstetrics offerings in hospitals across the region.

According to the Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 183 rural hospitals have completely shuttered operations since 2005. When a hospital closes in a rural community, it makes it difficult for that community to thrive. One of the initial signs of trouble for an ailing rural hospital is a reduction or elimination of labor and delivery services.

Women’s services closures are often driven by the sustainability of the service itself. Staffing an around-the-clock unit is difficult due to the shortage of health care workers. The absence of nearby maternity services results in longer travel times, higher costs and medical complications.

In 2019, an average of 47 babies were born per day across the 29 eastern North Carolina counties. Those babies represent the future of the communities in which they are born and live, signifying the importance of maintain hospital-based obstetrics and labor and delivery services.

Dr. Daniel Dwyer, an OB-GYN at Outer Banks Women’s Care, said he remembers a time when many mothers in the area used to deliver babies on the way to the hospital. He said having rural hospitals close to where patients are can make the difference for positive outcomes, especially for mothers and babies.

For those living in communities where specialist care may not necessarily be only a few miles away, it is important to find ways to bring services directly to them. At the Outer Banks Women’s Care clinic, Dr. Dwyer said the services they offer keep patients close to home while receiving leading-edge care.

“We have begun to see patients for perinatology consultations, which is an important part of coordinating care for our highest risk patients.” Dr. Dwyer said. “Historically, it would take more than a half day for patients to get a consultation with a maternal-fetal specialist. In addition to the travel, the setting and staff would be unfamiliar for the patient. There is increased anxiety, cost and potential for loss of key information when patients travel for services that can be delivered in their trusted medical home. We hope to continue to leverage the technology and professional relationships to provide specialist care in rural settings. I think this is but one large step in the right direction toward reducing the disparities in access to the highest quality of care for our patients.”

Supporting hospitals across the region

High-quality perinatal care and labor and delivery services are synonymous with the ECU Health name. Dr. James deVente, associate professor at Brody and medical director of obstetrics at ECU Health Medical Center and Angela Still, senior administrator for women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center, have helped lead a perinatal outreach team that takes high quality training and best practices into other hospitals across the region, including facilities not affiliated with ECU Health.

Since 2012, the outreach team has visited every hospital across the region and has helped smaller hospitals better prepare for expectant mothers and new babies with serious medical conditions. From 2018-21 alone, the perinatal outreach team visited 18 different hospitals across the region, hosting 169 simulation days and educating more than 500 students on advanced life support training, emergency simulations, electronic fetal monitoring and more.

According to Dr. deVente, these efforts are a necessary part of improving care, reducing infant mortality and helping eastern North Carolina thrive.

“Data shows us that when a woman has to travel more than 50 miles to a hospital, her outcomes are worse. Data also shows us that businesses want to come to communities where labor and delivery services are present,” Dr. deVente said. “At ECU Health, we designed the outreach program and cover the cost of this work with those realities in-mind. If we are going to solve the infant mortality issues that our region faces, we are going to have to work together with health care partners across the East. I’m proud to say we are leading the way in that regard and the work is truly making a difference.”

Innovations to bridge gaps

It is no secret that eastern North Carolina is a vast rural region with long travel times between communities. An innovative program launched in 2020 at East Carolina University is helping to make women’s telemedicine, telepsychiatry and nutritional support services more accessible.

The MOTHeRs Project was first offered to patients at primary care obstetric clinics in Carteret County and has since expanded to ECU Health and other clinics in counties across the region. Through formalized partnerships with clinics, patients in the practices are cared for by both an ECU specialist and their local physician through a combination of telehealth and face-to-face visits.

Dr. Dwyer and Outer Banks Women’s Care were the third clinic in the ECU Health system to join the MOTHeRs Project. Maternal-fetal medicine and behavioral health care offerings for expectant mothers has been a much needed addition to the practice.

“We have identified access to mental health care as the greatest need in our rural communities. This need is increased during pregnancy and the post-partum period. Providing this service is a huge addition to maternal health care,” Dr. Dwyer said. “We have already begun to have mental health appointments in our office through the MOTHeRs Project. The feedback from our patients have all been very positive. This is just the beginning of learning how to give the needed specialized care in rural offices.”

Through its ongoing work, the MOTHeRS Project expects not only to provide care to those who need it, but also to generate new knowledge regarding how barriers to care can be better addressed. It aims to be a national model to ensure that every woman in rural America has a safe and healthy pregnancy and delivery.

“ECU Health, Brody and East Carolina University are truly pioneering high-quality rural obstetrics and women’s care services,” said Dr. Michael Waldrum, ECU Health CEO and dean of Brody. “Our hospitals and clinics provide excellent care in communities across eastern North Carolina. The perinatal outreach team trains other smaller hospitals on emergency care, best practices and more. Telemedicine innovations like the MOTHeRs Project makes patient-centered care more accessible. I’m proud of the work that all team members do to help our mothers, babies and communities thrive.”

Resources

A pink ribbon is one of the most recognizable symbols in health care. This is because breast cancer, the disease for which the color represents, is the second most common cancer in women, affecting one in eight women. Breast cancer develops when an abnormal growth occurs within the breast tissue, typically caused by uncontrolled cell growth in the breast. These rapidly growing cells form a potentially cancerous lump or mass and can spread to other areas, including lymph nodes.

Breast cancer often presents as:

- A lump or mass in the breast

- A change in size or shape of the breast

- A change in nipple appearance, including a newly inverted nipple or discharge

“I encourage everyone to know and understand what their breast tissue should look and feel like so they’re aware of any potential change,” said Dr. Karinn Chambers, breast surgical oncologist, ECU Health and ECU’s Brody School of Medicine.

It is never too early to begin self-exams of the breast, according to Dr. Chambers. However, women should begin breast cancer screenings annually at age 40, according to the American Cancer Society. This consists of a mammogram, which is an x-ray of the breast.

Dr. Chambers also emphasized that everyone, including men, should be aware of their breast health.

“Anyone can get breast cancer,” said Dr. Chambers. “I have seen breast cancer in people of different ages, the young and the elderly. Men can also get breast cancer.”

While breast cancer in men is much less common than in women, the American Cancer Society predicts that about 2,710 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in men in the United States in 2022.

“When a man is diagnosed with breast cancer, typically they present with the same symptoms as women – a new mass or lump within the breast,” said Dr. Chambers. “The causes and risk factors of breast cancer in men and women are also very similar.”

Breast cancer has both unknown and known risk factors. While experts still do not fully understand all of what causes breast cancer, genetics and lifestyle play a role in breast cancer.

“We recommend that women and men with a close family history of breast cancer undergo genetic testing to understand if they have a mutation on either the BRCA1 gene or the BRCA2 gene,” said Dr. Chambers. “BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes prevent proteins from rapidly growing out of control, which can cause certain cancers. For those who have the mutation, we do recommend prophylactic bilateral mastectomies, or removal of both breasts, as a preventative means to try to reduce their risk of breast cancer.”

While genetic risk factors are out of an individual’s control, there are behavioral changes one can make to lower their risk for breast cancer. The first is eating a healthy diet and exercising.

“Obesity is a big risk factor for breast cancer, and the rise of obesity in our population has led to an increased risk of breast cancer,” said Dr. Chambers. “Excess alcohol use can lead to increased risk of breast cancer as well.”

Experts highly encourage individuals to discuss screening with their primary care providers to understand their own risk for breast cancer based on their hormonal history, family history, health and age. The early detection of breast cancer allows for less invasive treatments, a greater variety of options and a greater potential to prevent the spread of breast cancer. When a person is unfortunately diagnosed with breast cancer, there are a variety of treatment options.

“The treatment of breast cancer consists of local tools and systemic tools,” said Dr. Chambers. “Local tools like surgery and radiation target the tumor directly. Systemic tools such as chemotherapy and hormone therapy can reach cancer throughout the body and may be used if the cancer has spread beyond the initial breast tissue.”

The bottom line?

“To prevent breast cancer, an individual should first discuss screening with their primary care providers so that they understand when and how often to get breast cancer screening,” said Dr. Chambers. “The second part of that would be to understand their own risk for breast cancer. Lastly, always remember to practice self-exams and know what is normal for your breasts. If you experience any changes, notify your primary care provider.”

Early diagnosis and a variety of treatment options have largely increased the odds of curing and managing breast cancer. ECU Health continues to offer 3D mammography at ten convenient locations throughout our region. Patients can take advantage of ECU Health’s free online risk assessment tool, talk with a provider and schedule a screening that meets their needs.

To learn more, please visit ECUHealth.org/breast-cancer.

Vidant Beaufort Hospital, a Campus of ECU Health Medical Center and ECU Health Women’s Care, located in Washington, offered free breast cancer screenings on Friday, Feb. 25 for uninsured women 40 years of age and older with at least one year since their last mammogram.

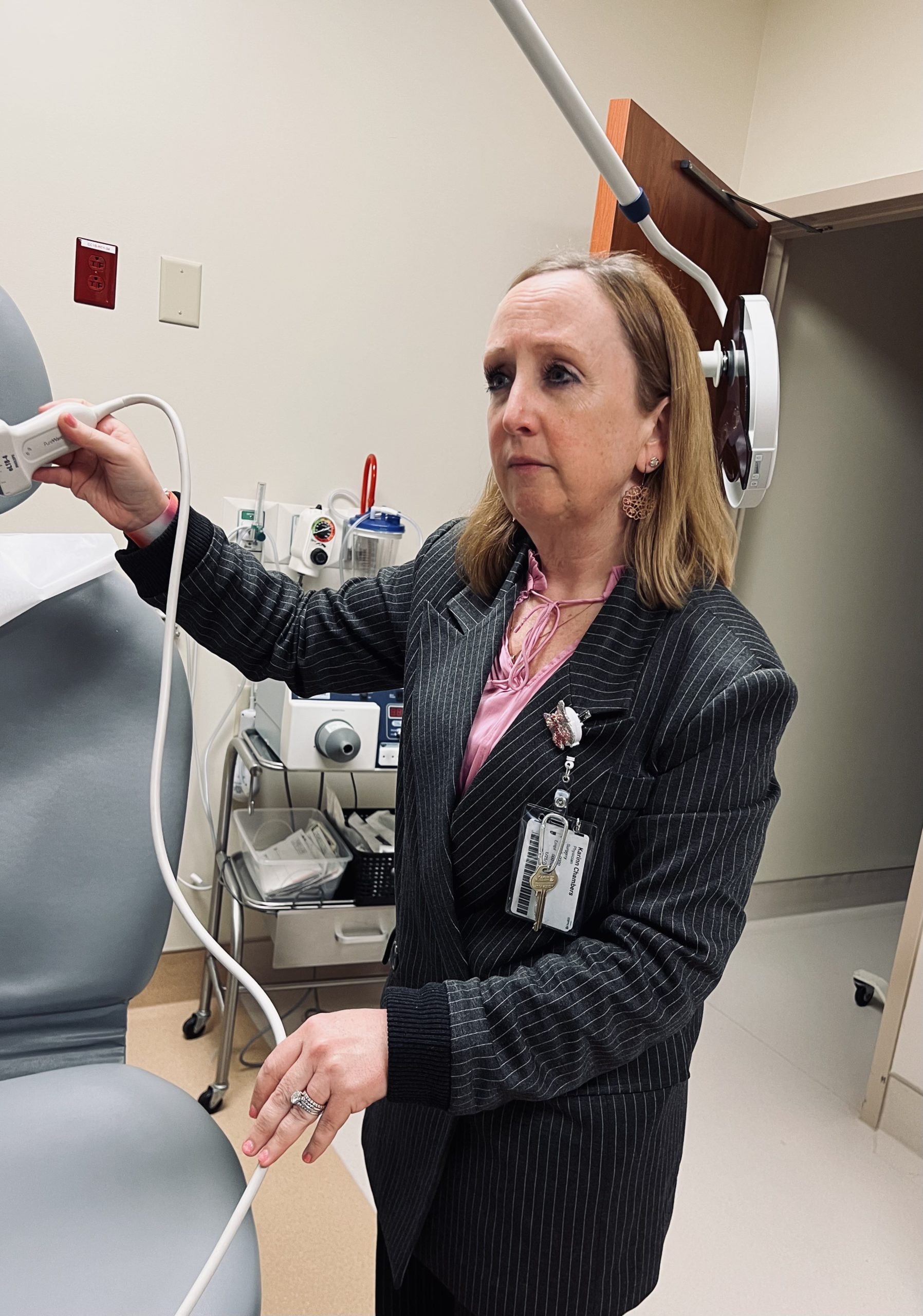

“Some of these patients have never had mammograms before, and some of them haven’t had one in many years,” said Caddie Cowin, DNP, FNP-C at ECU Health Women’s Care – Washington. “All of these patients are either uninsured, or their insurance does not cover breast cancer screenings.”

Patients received a clinical breast exam, mammogram and education on signs and symptoms of breast cancer to watch for. Mammograms are one of the greatest tools to screen for breast cancer, and early detection is proven to save lives. Even with monthly physical exams at home, mammograms can catch warning signs that go undetected. Yearly mammograms are recommended to begin at age 40, or age 35 if you have close family history of breast cancer. Breast cancer can be treated with better outcomes if caught early.

According to the Department of Minority Health, Black women were just as likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer, however, they were almost 40 percent more likely to die from breast cancer, as compared to non-Hispanic white women from 2014-18. An explanation for that gap, according to the 2020 census, could be health insurance. The percentage of the Black population with no health insurance coverage for the entire calendar year was higher than for non-Hispanic Whites, at 9.6% compared to 5.2%, according to the 2020 census. Bridging the health care gap to provide early clinical interventions is important in eastern North Carolina, where Vidant and the future Vidant Health serves a large, diverse region.

“The biggest challenge is access to care,” said Cowin. “We know that patients with a lower socioeconomic status struggle more with access to health care and insurance. The disparity is challenging, but this program can help address the need. Just because they cannot pay out of pocket doesn’t mean they can’t get as good care as anyone else.”

“The last clinic we did, a couple of patients ended up needing biopsies, so we were able to catch potentially dangerous things early,” said Cowin. “We could save somebody’s life with what we are doing.”

If a patient does have abnormal findings, the Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program (BCCCP) from the county health department funds follow-up appointments and connects women to treatment if diagnosed. BCCCP is designed to help uninsured or under-insured women pay for mammograms and pap smears, according to Sherri Griffin, RN, BCCCP nurse navigator, Beaufort County Health Department.

“If we do have any ladies unfortunately diagnosed with breast cancer, we help them apply for breast and cervical cancer Medicaid, which pays for their treatment,” said Griffin. “The women that we have treated today are in a gap where most cannot qualify for Medicaid but cannot afford health insurance. They typically put off health screenings because they have to pay out of pocket. At this event, we fill in gaps for the women who may need additional imaging after the initial screenings.”

Screenings at this event were funded by the Shepard Cancer Foundation and Vidant Health. For more information on cancer screenings, please visit VidantHealth.com/Cancer. More information about BCCCP can be found at BCHD.net.

Read more in The Washington Daily News.

The cervix is the lower, narrow end of the uterus and when cancer starts in this area, it is called cervical cancer. Each year more than 350 North Carolina women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and over 100 die from the condition, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. The majority of these deaths occur in women over the age of 45.

Although cervical cancer starts from the cells with pre-cancerous changes, only some of the women with pre-cancer of the cervix will develop cancer. For those that do, treating cervical pre-cancers can prevent almost all cervical cancers.

Dr. Grainger Lanneau, chief of gynecology oncology at Vidant Health/ECU Health Cancer Care said, “The two most important things to do to prevent cervical cancer are to get the HPV vaccine if you are eligible, and to be tested regularly according to American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines.”

Pre-cancerous changes can be detected by the Pap test and treated to prevent cancer from developing. The HPV test looks for infection by high-risk types of HPV that are more likely to cause pre-cancers and cancers of the cervix. HPV infection has no treatment, but a vaccine can help prevent it.

These tests are done in the same way with a special tool used to gently scrape or brush the cervix to remove the cells for testing. If pre-cancer is found, it can be treated, keeping it from turning into a cervical cancer. The result of the HPV test, along with past test results, determines your risk of developing cervical cancer. If the test is positive, this could mean more follow-up visits, more tests to look for a pre-cancer or cancer and sometimes a procedure to treat any pre-cancers that might be found.

For more information about the risks and prevention of cervical cancer, or if you do not have a primary care provider, please contact the Prevention Clinic at ECU Health Cancer Care (252) 816-RISK (7475).