Doctors, nurses, therapists — none can do their clinical jobs without facts: proof, by way of blood tests, X-rays and hands-on observations in order to determine a clear path forward to progress a patient to wellness.

The acute skills of observation and diagnosis are critical for the individual patient, but before health care providers can make clinical judgements and chart a path forward for their patients, health care as a whole needs facts. The facts that systemic health care requires comes in the form of research, which has given us modern medical wonders like antibiotics, MRIs, gene editing and thousands of other discoveries and inventions that have made historical medical death sentences into minor inconveniences.

The tradition of research in the pursuit of making health care better, particularly for those in rural and underserved communities in eastern North Carolina, is alive and well at East Carolina University and ECU Health. Here are a few examples of how Pirate researchers are improving lives one study at a time.

Women living with HIV

Dr. Courtney Caiola, an assistant professor at ECU’s College of Nursing and researcher focusing on women and HIV, said that that the HIV epidemic has made an insidious shift, from largely affecting urban populations in the epidemic’s early days to now having taken root in rural and underserved regions — eastern North Carolina has become a ready refuge for the disease.

The National Institute of Nursing Research has funded one of Caiola’s research projects that aims to find out how best to communicate with women living with HIV in rural settings, particularly for those without reliable access to high-speed internet connectivity.

Caiola is fighting an uphill battle, one complicated with social mores and community stigma for residents of rural and underserved area who are diagnosed with HIV.

“The epidemic has changed over the years, in good ways,” Caiola said. “People living with HIV are living really well now, but women living with HIV in the South have some of the highest rates of HIV infection but the lowest rates of viral suppression, which means that that they’re not engaged in care.”

Cultural barriers and social stigma often prevent many women in the South from seeking care, Caiola said. Women in a more urban setting might be able to visit an HIV clinic with little fear of disclosing her HIV status, but that isn’t necessarily the case when community members know which clinics serve patients living with HIV.

Caiola’s research partners well with an outreach and research project spearheaded by Dr. Leigh Atherton, an associate professor in the Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies at ECU’s College of Allied Health Sciences.

Atherton endeavors to find ways to prevent the spread of HIV in rural North Carolina by encouraging those in high-risk substance use groups to seek treatment for their addictions. Atherton’s team partners with community-based HIV outreach groups and supplements testing supplies, which puts his counselors in direct contact with at-risk populations.

One of the highest hurdles to clear for researchers focused of HIV treatment and prevention in North Carolina is simply getting enough people to participate in the research.

“There’s something called courtesy stigma. A lot of women with HIV are mothers and they don’t want the stigma that they might experience to be passed on to their kids, so they tend to keep very low profiles and be a bit socially isolated,” Caiola said, which necessitated her team partnering with multiple other HIV researchers in North Carolina and across the South.

Initial research findings suggest there is no one-size-fits-all solution to communicating with HIV positive women in rural areas.

“As clinicians, the differences in the way people respond to their circumstances is often very clear, but in research, people are often grouped into broad demographic groups for the sake of generalizability,” Ciaola said. “In fact, two women with similar demographic profiles, like Black women living with HIV in a rural area, may have wildly different responses to dealing with HIV.”

Disease prevention

For Brody School of Medicine Drs. Greg Kearney and Doyle ‘Skip’ Cummings, health-related research orbits around overarching conditions that spiderweb across the body creating a cascade of adverse consequences — hypertension and environmental public health.

In order to find ways to address the high levels of hypertension in rural areas, Cummings is piloting a program, in collaboration with UNC-Chapel Hill and the University of Alabama, to test home health reporting technologies that can identify high blood pressure patterns and upload those readings into a computer system for a team of health care providers to evaluate.

“Instead of just one provider seeing a patient every three months or so in the office, we’ve got a team of people that are trying to stay on top of blood pressure values and recognize when a patient’s blood pressure patterns appear to be out of control, signaling the need for quick follow up, often by telephone or telehealth,” Cummings said.

In setting patients up with the telehealth devices being tested, researchers are using the in-person meetings as an opportunity to gather baseline information that can be used to identify some of the causes of hypertension in disadvantaged and rural communities.

“We’re using screening instruments during the baseline visit to look at the social determinants of health — food insecurities and transportation and housing instability,” among other data points, Cummings said.

Cummings, a Brody professor of public health and the Berbecker Distinguished Professor of Rural Medicine, said that the amount of data that the system transmits from a patient’s home to the central computer is so small that the team has had no problems thus far with getting data to the health care team.

“I just came back from two days of site visits out in the mountains in rural North Carolina and we took the blood pressure cuff with us,” Cummings said. “We drove all over the mountainous areas and tried the blood pressure cuff in multiple places, and we didn’t have any problems. Part of it is because that blood pressure value is a very small amount of data. It’s not like you’re sending a video or pictures.”

Kearney’s research is rooted in a desire to understand environmental and occupational impacts on human health, particularly asthma and the effects of chemicals and pesticides on farm workers.

Kearney, an associate professor of public health at Brody and founding director of the school’s Environmental and Occupational Health Program, is working with a toxicology researcher at UNC-Charlotte, who has developed a portable medical device that can be used to test for pesticides in human blood.

Kearney said that they have pilot tested the device with farm workers working with different crops.

“Because of the nature of their work, they are in the fields daily during the season, and are at high risk for exposure to pesticides,” Kearney said. “Some pesticides are quickly metabolized in the body’s systems, so a person who is exposed and located in a rural area may have difficulty getting tested right away. With a simple finger stick and a drop of blood, this device can quickly alert you to pesticide exposure.”

Last year, Kearney organized a team and worked with community partners to conduct a regional community health needs assessment for the eastern part of the state. The project included working with representatives across 33 mostly rural North Carolina County health departments and ECU Health.

This research is critical for not-for-profit hospitals, which are required by law to complete community health needs assessments every three years, to understand how to plan for health care investment.

“The community health needs assessment and outcomes is a very serious process,” Kearney said. “It provides a mechanism for hospitals and communities to come together and decide how to invest funding with community-based organizations to address the most pressing health care related problems in their communities.”

Fresh start

In eastern North Carolina, people with Type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to die as the rest of the state and the country.

Fresh Start, a research and outreach project established by Dr. Lauren Sastre, associate professor of nutrition science at the College of Allied Health Sciences, partners with free clinic members of the North Carolina Association of Free and Charitable Clinics across 11 counties in eastern North Carolina. The research and outreach program aims to prove is that diabetes can be controlled by layering previously disparate approaches to diabetes management — providing healthy food to those in need, teaching patients how to incorporate food and exercise into their lives and building accountability structures.

“I’m from North Carolina, and I don’t want to keep seeing that we have diabetes in this region that is out of control,” Sastre said. “There are problems that are hard to solve and this one isn’t hard to solve — it’s just whether or not we are actually going to do it.”

Sastre and her expansive interdisciplinary team of dozens of ECU students, trainers and researchers hope that through teaching patients healthy ways to cook and how to put structures for accountability in place, the Fresh Start program could help patients learn to more effectively manage their disease.

“The question we asked ourselves was, ‘Can these things that other people have done individually, that have shown some effect, complement each other and should the synergy be more impactful?’” Sastre said. “It turned out to be what we hoped it would be.”

The first challenge, exposed early in the research process, was to get to diabetes patients where they were. Sastre’s team found, through face-to-face engagement with patients, that many in rural communities have a very real lack of digital connectivity.

“Everything is done over the phone with health coaching, and we’ve even moved in-person classes to the evenings,” Sastre said. “A lot of our folks are considered the working poor and they make just enough to not have a lot of help and they can’t go to classes in the morning or afternoon.”

Sarah Elliott, a junior studying nutrition science and a Fresh Start volunteer, was heartened by the progress that her patients made.

“We have received really positive patient feedback from the group classes and the health coach experience. People are saying, ‘Not even my own family care as much about my health as my health coach did,’” Elliott said. “It has been impactful to see the difference that this is making in people’s lives.”

And what does the initial research of this integrated approach to diabetes management show?

A1C, one of the blood markers of the body’s control of blood sugar, will typically go down one to one and a half percent with Metformin, which is the standard medication that diabetics are put on initially. The Fresh Start program’s mean decline in just four months was 1.87 percent, which is significant accomplishment that Sastre credits to the program’s multi-layered approach to food and lifestyle management.

“The patients enrolled in our program, their blood sugar control improved for some almost double what it could with some medications,” Sastre said. “Our patients also had reduced hospital re-admission rates, so we know that the program is working. It’s addressing diabetes and improving quality of life. It’s making an impact on disparity.”

Brandon Stroud, a doctoral student, knows farming in eastern North Carolina. He grew up on a farm near Dunn and his grandfather worked several hundred acres of land close to where Stroud was raised.

Undergraduate students, Stroud said, are taught in classrooms the skills they will need to be effective in a hospital setting. Research skills students learn working with patients in the Fresh Start program helps them to evaluate the effectiveness of integrating the three pillars of the program, which makes book learning real.

“This is different than lab-based research,” Stroud said. “It’s community-engaged research, right? So, you’re working with many different partners out in the community — clinics, farmers and different organizations. It teaches us the life skills that we need to be beneficial moving forward whether we want to go into business or continue down a clinical route. The research validates our personal experiences when we are able to employ rigorous evaluation and report these meaningful outcomes.”

Mount Airy, North Carolina, sits three miles south of the Virginia state line, a community of 10,000 so prototypical of Southern charm that it’s accepted as the basis for the town of Mayberry from “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Surry County — where Mount Airy is located — is considered a dental health professional shortage area, along with the rest of North Carolina, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration.

When Dr. Laura Mercer, a native of Mount Airy, graduated from East Carolina University’s School of Dental Medicine in 2019, she headed back to her hometown to practice — a native daughter returning to care for the community that raised her.

“It’s such a humbling experience to be able to serve the community that helped shape me into who I am today,” said Mercer, a dentist at James H. Wells, DDS. “I love being able to connect instantly with my patients when I tell them I am from Mount Airy. It’s a great first step to building lifelong relationships with my patients.”

Mercer is a prime example of the dental school’s mission to develop leaders with a passion to care for the underserved and improve the health of North Carolina and the nation. In the past four years, the School of Dental Medicine has won two national awards for its innovative model of education and patient care — one for placing eight community service learning centers (CSLCs) in communities across the state, and the other for its commitment to advancing social mission and exploring ways to better serve rural parts of the state.

The school’s earliest vision — when the idea of a dental school in Greenville was still picking up steam in the 2000s — included a promise to educate new dentists who were naturally inclined to remain in North Carolina and practice in rural and underserved parts of the state. The school’s system of CSLCs was a built-in part of that mission that soon became tangible. More than a decade later, the model has yielded solid results and credibility to the school’s commitment to immerse students in the challenges and rewards of practicing in rural locations.

Those relationships are built from the ground up before students leave the ECU School of Dental Medicine.

Fourth-year dental students spend nine weeks in three different CSLCs across the state, for 27 weeks of experience living and working in communities whose residents face a plethora of disparities, from financial hardships to geographical access— in addition to other obstacles in the way of care for many socially disadvantaged patients.

The CSLCs, campus and hospital clinics and other locations have enabled the school’s faculty, students and residents to care for more than 92,000 patients from all 100 of the state’s counties. Close to 90 percent of the school’s more than 400 alumni are practicing in North Carolina.

“We envisioned, very early on, a model of education and patient care that would not only address the oral health care gap in North Carolina but also instill in future dentists a desire to put their talents to work in rural and remote communities,” said Dr. Greg Chadwick, dean of the ECU School of Dental Medicine. “We will continue to create pathways to oral health care in rural communities as we encourage our graduates to practice within reach of all North Carolina patients who need them.”

From the Appalachians to the Atlantic

As part of her dental school experience, fourth-year dental student Kari Wordsworth has lived and worked in the communities of Spruce Pine in the mountains and Brunswick County in the southeast corner of the state. Two of the school’s CSLCs are in those areas — the others are in Ahoskie, Davidson County, Elizabeth City, Lillington, Robeson County and Sylva.

“It’s empowering to physically be living out our dental school mission,” Wordsworth said. “Getting to be a part of what our school is doing — providing a sustainable model to provide care to these rural areas where otherwise they may not have access to care near them has been so rewarding.”

Caring for patients on opposite ends of the state has shown Wordsworth that while dental patients can face many of the same challenges and socioeconomic barriers to care, their rural communities are different in many ways — presenting additional considerations when exploring the best route of care.

“I have better understood that different patient populations have different needs, and they can become pretty unique,” she said. “Here in Spruce Pine, we see a lot of kids, whereas in my time in Brunswick (County), I saw a lot of folks who have retired. Ahoskie had a lot of special needs patients.”

That exposure to different populations can contribute to graduates’ decisions to practice where they are needed most.

“In North Carolina, where all 100 counties are health professional shortage areas, no matter where students go there are going to be underserved populations that they need to know about and understand how to best get them in for care,” said Dr. T. Rob Tempel, the dental school’s associate dean for extramural clinical practices. “What’s unique about ECU’s model is our students live for 27 weeks out in these rural communities, and the teammates they work with live in these rural areas. The students get to build relationships with them and see what’s important to them and their families and friends in the rural areas.”

In addition to the CSLC communities, students, faculty, staff and residents are spending time in counties with few or no practicing dentists. The Bertie County School Based Oral Prevention Program, a program based on a grant from the Duke Endowment, works to provide long-term oral health care and build positive dental hygiene habits in school children in that community. A similar program is slated to kick off in Jones County early next year.

Earlier this year, the School of Dental Medicine opened a small clinic in Hyde County to offset the lack of access for people from the region and to strengthen the ties between oral health and primary care.

“What really makes us unique is we include the communities in the conversation in order to build sustainable solutions for us to keep the promise that we have with the state for our dental school, by getting feedback from the stakeholders, including them in developing solutions and everybody’s challenges and opportunities are understood,” Tempel said. “Hyde County is a perfect example of that; we involved that community and we’re continuing to make a difference.”

Tempel added that trust is a key factor in reaching rural and underserved communities.

“It’s also really important to understand the value of trust and what you need to do to establish that with the people in these communities to be successful in meeting their needs,” he said. “We have to be part of the primary care system — and in rural areas, that’s amplified. Everyone has to work together to be successful in getting through these barriers to care.”

Reaching out and leaning in

Three years into her career, Mercer feels secure in her academic and clinical foundation built at ECU.

“The School of Dental Medicine helped me succeed as a dentist in a rural area of the state by making me a well-rounded professional,” she said. “The program did a great job of making sure I became competent in all areas of dentistry so that I could provide most services to patients without having to send them miles away.”

After earning a degree in molecular biology in 2016 from ECU, Dr. Darian Askew graduated from the dental school in 2022 and practices in Roanoke Rapids. Originally from Hertford County, Askew completed a rotation at the CSLC-Ahoskie. He credits the dental school with teaching him how to interact with people from different backgrounds, cultures and places.

“I don’t believe I would be exposed to the same level of cultural variation at a school localized to one area,” he said before graduation. “Being able to relate, empathize and interact with people on almost any level, I believe is a great trait to have, and probably my greatest strength now.”

More of that exposure also comes from programs that support rural patients who may be in search of a dental home — an office they can establish with and return to for routine care. Since 2018, the school’s ECU Smiles for Veterans events have provided care for nearly 250 veterans. The Sonríe Clinic, held at Ross Hall, provides care for migrant farmworkers from eastern North Carolina. Many students and faculty participate in North Carolina Dental Society Foundation Missions of Mercy clinics across the state that offer free or low-cost care. Others travel as part of “mobile clinics” that provide care during events across the East.

New and existing partnerships with local and state organizations and institutions also help the school reach rural and underserved areas.

“ECU values the partnerships with the dental societies, other educational institutions, oral health collaboratives, community colleges and the many private funders that see the value of health care,” Tempel said. “We certainly serve as a model for how this can be done effectively and collaboratively. Our relationship with community colleges is absolutely an example to others on how we can develop the work force and get them back in rural areas.”

Chadwick said much of the success of the dental school during its first decade comes from relationship-building, solution-seeking and action-taking.

“Addressing better access to health care for rural and underserved communities is not something we can do alone. It takes partnerships and collaborations with stakeholders across the state, and the School of Dental Medicine has been building those relationships since its planning phases,” Chadwick said. “By working together, thinking creatively and acting purposefully, we are meeting our patients where they are — and we’ve been able to do that because we have become a part of their communities and their lives.”

The college and schools on East Carolina University’s Health Sciences Campus share a mission produce top-notch health care professionals to serve North Carolina.

A key component of that commitment is innovation in delivering education and patient care in the most rural and underserved communities, as well as rural health-focused courses, field work, research and programs that emphasize the need for better access across the state

ECU’s innovative rural health focused education is taking place across North Carolina, from nursing students caring for Alzheimer’s disease patients in the East to the rotations dental students complete community service learning centers in the mountainous western portion of the state.

Here’s a look at how the colleges and schools on ECU’s Health Sciences Campus are addressing North Carolina’s rural health care needs and challenges through education.

College of Allied Health Sciences

In the College of Allied Health Sciences, patient care includes valuable learning experiences for students on how to provide care in rural settings and for patients from rural communities. Rural health care is central to the school’s mission.

“Our students learn about the importance of transforming health care, promoting wellness and increasing access to health care for the people of eastern North Carolina,” said Dr. Leigh Cellucci, associate dean for academic affairs. “Students spend time with patients and clients from rural areas. They learn firsthand the importance of access to health care.”

ECU’s College of Allied Health Sciences is North Carolina’s largest allied health sciences college at a four-year institution. It has a fall 2022 enrollment of 1,481 students and boasts more than 10,000 alumni. Close to 75 percent of its graduates remain in North Carolina to work, with just over half of those working or living in eastern North Carolina.

The school’s clinics, including the Speech Language and Hearing Clinic, the Student-Run Physical Therapy Clinic, the new Student-Run Occupational Therapy Clinic and the Navigate Counseling Clinic see patients from rural areas of eastern North Carolina. Other initiatives created in the college are aimed at addressing health care challenges for special populations.

Rural health is a key component across the school’s departments in order to prepare students for careers anywhere they are needed.

“It is of critical importance that small hospitals in eastern North Carolina employ highly qualified clinical laboratory science professionals to work in their labs to provide better health care,” said Dr. Guyla Evans, chair of the Department of Clinical Laboratory Science. “The people of eastern North Carolina deserve this, and we accomplish this.”

Dr. Paul Bell, professor in the Department of Health Services and Information Management, said preparing students through curriculum and experience will enable them to better understand the importance of access in improving health care services.

“Health care administrators serve an important supportive role to ensure better health for the people who live in our rural communities, and our understanding that access to primary care, particularly preventive care, will improve our health is central to our mission of transforming health care delivery,” he said.

Physician Assistant Studies student Allision Priest said the college not only prepares students but provides them invaluable resources to assist patients that will be relevant into their future careers.

“[Our faculty are] not only inspiring us to work in those rural fields, but they’re also giving us resources to be able to help the people that are living in those places,” Priest said. “We’re really diving deep into health inequities and understanding food deserts.”

The Brody School of Medicine

The Brody School of Medicine educates students about the obstacles patients in under resourced must overcome to receive health care.

“The majority of the counties in this state are rural, so if we are going to proclaim to improve the health status of eastern North Carolina we have to be prepared to do so in a rural environment,” said Dr. Matthew A. Rushing, family medicine clinical assistant professor and assistant residency director.

The school values recruiting mission-fit students with a rural background, experience with underserved populations and a track record of community and service engagement.

Brody is over the 90th percentile nationally in graduates practicing in rural areas with 12 percent of graduates practicing compared to a national median of 4 percent, according to the AAMC Mission Management Tool. Brody also has the highest retention of graduates practicing in rural North Carolina counties five years after graduation among other medical schools in the state, according to the Sheps Center report on 2022 Outcomes of NC Medical School Graduates.

With more Brody graduates practicing in the state than any other medical school it is a testimony to the school’s mission, Rushing said.

“This work is more than important – it’s necessary, and this is where Brody education truly shines,” Rushing said.

Training for service in rural areas starts as early as the first year of medical school for Brody students, with a series of standardized patients whose stories are set in the rural communities of eastern North Carolina that first-year students encounter as they learn to conduct patient interviews as a first step in diagnosing patients.

First and second-year Brody students are offered a course on Society, Culture, and Health Systems that includes research project that focuses on county health systems. Students gather data on one county health system and population, use the data to examine the county’s COVID-19 response and develop and answer a research question related to the health system as it relates to course concepts.

“The purpose of this project is to bring the topics and concepts covered in our course to life a real and local way,” said Dr. Sheena Eagan, course director and assistant professor. “The project highlights the vast differences between rural, urban and suburban counties, reinforcing the idea that counties can be adjacent and yet have vastly different health systems contributing to disparities in health status.”

The course helps students examine the barriers to optimal health that residents face in rural North Carolina.

“Students examine the health care systems currently in place and determine if there are better ways to deliver quality healthcare to populations that are in these settings,” said Dr. Cedric Bright, interim vice dean and associate dean for admissions.

Second-year students also examine how to better address the lack of access from hospitals closing as well as private practices, and how that impacts preventive medicine and population health.

As they move into the third and fourth years, Brody’s Family Medicine Clerkship places students in community clinics where they see first-hand how rural physicians care for their patients. Students on their Family Medicine and Pediatric clerkship rotations spend up to half of their training in a rural, community setting. Medical students are assessed on their ability to communicate with patients in a caring, compassionate, and effective manner.

Students may choose from a variety of elective courses to gain exposure to a variety of medical specialties and explore individual interests. Students can participate in an elective led by BSOM faculty to serve rural communities in Zambia, which allows students to serve the needs of an international community. Students can also complete a combined Internal Medicine/Pediatrics Acting Internship at ECU Health Duplin Hospital or ECU Health Edgecombe Hospital.

“Rural medicine requires an element of ingenuity — patients living in rural areas have health care needs that are shaped by the resources they are (or aren’t) able to access easily in their communities,” said Emmalee Todd, a third-year medical student. “Even for those of us who will end up at large tertiary-care centers, understanding what goes into rural medicine can help us better serve patients coming from those areas.”

In the fall of 2021, Brody and ECU Health Medical Center (formerly Vidant Medical Center) launched a new Rural Family Medicine Residency Program to equip physicians with specialized training in caring for patients in rural and underserved communities.

Residents spend a majority of their first year of training at ECU Health Medical Center and ECU’s Family Medicine Center in Greenville before spending the next two years training in rural health care centers in eastern North Carolina.

The complete Brody experience provides an integrated curriculum focused on health systems science for all four years, adding to students’ foundation for practicing rural health by using an authentic, embedded approach to patient safety, population health and team-based care.

“Ultimately, we hope that from this curriculum, the next generation of leaders will arise to meet the needs of the people in eastern North Carolina,” Bright said.

Department of Public Health

The Department of Public Health at the Brody School of Medicine provides a strong foundation of understanding the challenges of rural health.

“The needs of rural people are distinctly different than those in urban or more urban communities,” said associate professor Dr. Ruth Little. “In order to successfully facilitate rural health improvements, this population has to be first understood.”

The department requires Master of Public Health students to take a course on Interdisciplinary Rural Health, which includes topics from the concentrations of epidemiology, health policy and leadership and community health and health behavior.

“In epidemiology, we lay the groundwork for rural and urban comparisons, ultimately demonstrating that for many health indicators rural communities suffer a higher burden of disease than their more urban counterparts,” said Dr. Nancy Winterbauer, associate professor. “In health policy and leadership, we examine reasons for these disparities, including the impact of race, access to health services and policy on rural health. Finally, the community health and health behavior concentration focuses on rural health improvement, especially in the areas of health behavior, community engagement and advocacy, evidence-based interventions and public health practice.”

Little said rural communities in the East have a bleaker health outlook than the regions in the middle and western portions of the state.

“It’s important to help our students not only understand this, but in addressing these health disparities, engage students with rural communities, providing opportunities for us to work together to improve population health,” said Little.

Student Brandon Stroud said the curriculum in rural health is preparing him to be able to think critically to solve problems in rural communities.

“Often, these counties have a much lower median income compared to their urban counterparts, there are fewer healthy food resources, recreational spaces, less health care providers and limited access to specialty care,” he said. “All these factors simultaneously cause higher incidence of chronic illnesses and poor health outcomes. That is why it is so critical we learn about these issues, how rural health care systems are working to address them and urge more public health practitioners and health care providers to serve them.”

The College of Nursing

ECU’s College of Nursing graduates close to 79 percent of nurses employed in North Carolina, with 39 percent serving eastern North Carolina. Nearly 60 graduates chose to work in one of the state’s 40 most distressed counties, as designated by the North Carolina Department of Commerce.

Specific nursing courses and programs encourage students to gain exposure to health care settings where they will care for patients from every life situation.

“In community health, we ensure that our students are prepared to take care of patients in all environments,” said Lesha Rouse, clinical instructor. “In this course, the student will complete a Community Service Learning Project (CSLP), expanding perspectives of ‘health care’ from the individual, acute care focus to a population-, community-based focus.”

Nursing students at every level receive instruction and experience caring for patients in rural settings.

“Students are training in a number of ways, including traditional lecture and course content as well as through experiential and simulated learning,” said assistant professor Dr. Stephanie Hart. “This is particularly important relative to practice in rural areas, where students are exposed to the realities of the social determinants of health — the primary drivers of population health outcomes.”

Hart said undergraduate students prepare to enter clinical rotations in rural areas by learning about the social determinants of health and the unique needs of rural communities.

“They build upon their knowledge of rural health through their participation in a windshield survey of an eastern North Carolina county, which provides them with the opportunity to drive around the county making observations of community members and their environment,” she said. “From there, they continue to explore these communities in detail through review of the county community health needs assessment and engaging with community members and key stakeholders to gather insight into community strengths and needs.”

The majority of undergraduate students, including those in traditional BSN and accelerated BSN programs, complete an 85-hour clinical rotation in community health or community-based settings to further add to their experience in rural areas.

“They are able to successfully integrate into the clinical learning environment, where they not only learn more about the unique needs of the individuals and communities served by these agencies, but they are afforded several opportunities to apply course objectives in practice,” Hart said.

She added that ECU’s College of Nursing and one of its partnering clinical agencies, 3HC Home Health and Hospice Care, Inc., received funding from the Hospice and Home Care Foundation of NC to participate in a pilot project designed to address the shortage of home care nurses across North Carolina, particularly in rural areas.

“This project resulted in new approaches regarding the training, recruitment and integration of newly graduated RNs into home health and hospice agencies,” Hart said.

The college has also received funding from Eastern AHEC for the last several years to develop new clinical training sites for nursing students, most of which are situated within rural, underserved Tier 1 or Tier 2 counties.

Hart said these programs and curricula offer students exposure to prepare them to work in those same settings as professionals.

“When we train health care professions students to work with and understand community health and rural health care, we aim to eliminate these gaps by facilitating recruitment and retention efforts of health care professionals in rural areas, reduce workforce shortages and increase diversity in our workforce,” she said.

The college also has a Health Resources and Services Advanced Nursing Education Workforce grant that allows the college to train a select number of advanced practice registered nurse students to care for patients in rural and underserved areas, including patients who are farmers, loggers and fishers — occupations prevalent to North Carolina that also present industry-specific health hazards. The program, APRN Rural and Underserved Roadmap to Advance Leadership (RURAL) Scholars Program, includes a graduate-level course in agromedicine with practical experiences with the farming community.

“Students are provided generous stipends to participate in the program, which includes instruction in rural health and health disparities, clinical practice in rural and underserved communities and training in telehealth and telepsychiatry,” said Dr. Pamela Reis, associate professor and interim Ph.D. program director in the College of Nursing.

So far, 47 students have graduated from the program and are providing care in these communities across North Carolina; there are 17 students in the current cohort.

Dr. Michelle Skipper, director of the doctor of nursing practice program, said educating nurse practitioners to the needs of rural patients is critical for the transformation of the region’s health care delivery.

“We can recruit nurses from rural communities, train them as primary care clinicians, and return them for long-term service to the community which already trusts them,” Skipper said. “Receiving care from a nurse practitioner is ultimately an ideal choice in small towns, not simply a ‘consolation prize’ because other health care professionals don’t want to live and work there.”

Dr. Donna Roberson, professor and director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, Carolina Geriatric Workforce Enhancement program grant, said it is crucial to educate nurses about the aging population and some of the diseases that are more prevalent among older adults.

“As our eastern North Carolina citizens age, their risk for dementias like Alzheimer’s Disease increase,” she said. “Most are living in their communities and are cared for by family caregivers. Their health care providers (medical doctors, nurse practitioners and more) need to have a good understanding of what the person living with dementia experiences and what their family has to manage.”

The third Thursday of November is National Rural Health Day and ECU Health and the Brody School of Medicine are celebrating team members, faculty, staff and students by shining a light on the work they do to make a positive difference in the lives of the 1.4 million people living in eastern North Carolina.

A note from ECU Health CEO and Brody Dean Dr. Michael Waldrum: National Rural Health Day is a day to shine a light on the contributions of rural health professionals across the country. We created ECU Health earlier this year with high-quality rural health care in mind. The team members who work here truly personify the region and we wanted our name and logo to reflect that. We wanted our patients to know that the care we provide is backed by the educational excellence taking place at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University. More than anything else, we wanted eastern North Carolina to know that ECU Health will always represent them. That’s a testament to the more than 13,500 ECU Health and Brody team members, who embody our mission and serve our communities. Thank you for your service and commitment to our organization, region and patients.

ECU Health serves a vast rural region made up of 29 counties and home to more than 1.4 million people. Like many rural regions, people across eastern North Carolina face a number of systemic socioeconomic challenges which have negative impacts on health outcomes. Perhaps most tragic of all, the region has wrestled for years with higher infant death rates than the state average, driven by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, barriers in access to care and fewer local resources to support expecting mothers.

Dr. Madhu Parmar, an OB-GYN for ECU Health, practices in Ahoskie. She helps facilitate countless healthy deliveries, but the ones that don’t go as planned stick with her the most. That is because many of the complications are preventable, and adequate access to perinatal care helps facilitate positive outcomes for both mother and baby. The unfortunate reality is that rural and underserved communities simply lack access to the perinatal care they need.

“This issue is very personal because I feel like there are not enough resources, people and attention placed on caring for mothers and babies in rural areas,” Dr. Parmar said. “I feel like rural mothers and babies are the ones that need care the most and we must do all we can to ensure they have access to that care. You hear about smaller hospitals closing down their OB units and that just increases the risk to mother and baby. If a community has access to these services, you see how the mother and the baby can thrive. That’s what we’re aiming for at ECU Health, access for all.”

Dr. Parmar says the primary challenges she sees in her patients stem from poverty. Data tells us that 1 in 4 mothers in eastern North Carolina live below the poverty line and 1 in 8 are uninsured.

“Because of poverty, patients are not as healthy,” she said. “Obesity and chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, are the things presenting difficult challenges for normal patients, and those conditions are even more challenging for pregnant patients. The reality is that we take care of a lot of high-risk patients in the East because many of our patients experience poverty.”

Across the region, more than 50 percent of the mothers delivering babies at ECU Health hospitals are clinically overweight. In Ahoskie, where Dr. Parmar practices, the average Body Mass Index (BMI) is about 40, nearly 15 points higher than the high range of a healthy person.

Keeping patients informed and educated about their health has been a key focus, Dr. Parmar said. Understanding illnesses and what to watch for is half the battle; a healthy mom often times leads to a healthier pregnancy.

“A nurse who specializes in diabetes care comes to our office once a week to educate our patients,” Dr. Parmar said. “She teaches them how to monitor their blood sugar and how to improve their diet so that we have optimal outcomes for the babies. She works with our nurses, too, and makes sure they’re looking through patients’ blood sugar diaries when they come in. The biggest thing we can do is be available to these patients.”

Women’s care close to home

At a time when many rural communities across the United States are losing access to obstetrics and women’s care services, ECU Health is doing its part to maintain and enhance obstetrics offerings in hospitals across the region.

According to the Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 183 rural hospitals have completely shuttered operations since 2005. When a hospital closes in a rural community, it makes it difficult for that community to thrive. One of the initial signs of trouble for an ailing rural hospital is a reduction or elimination of labor and delivery services.

Women’s services closures are often driven by the sustainability of the service itself. Staffing an around-the-clock unit is difficult due to the shortage of health care workers. The absence of nearby maternity services results in longer travel times, higher costs and medical complications.

In 2019, an average of 47 babies were born per day across the 29 eastern North Carolina counties. Those babies represent the future of the communities in which they are born and live, signifying the importance of maintain hospital-based obstetrics and labor and delivery services.

Dr. Daniel Dwyer, an OB-GYN at Outer Banks Women’s Care, said he remembers a time when many mothers in the area used to deliver babies on the way to the hospital. He said having rural hospitals close to where patients are can make the difference for positive outcomes, especially for mothers and babies.

For those living in communities where specialist care may not necessarily be only a few miles away, it is important to find ways to bring services directly to them. At the Outer Banks Women’s Care clinic, Dr. Dwyer said the services they offer keep patients close to home while receiving leading-edge care.

“We have begun to see patients for perinatology consultations, which is an important part of coordinating care for our highest risk patients.” Dr. Dwyer said. “Historically, it would take more than a half day for patients to get a consultation with a maternal-fetal specialist. In addition to the travel, the setting and staff would be unfamiliar for the patient. There is increased anxiety, cost and potential for loss of key information when patients travel for services that can be delivered in their trusted medical home. We hope to continue to leverage the technology and professional relationships to provide specialist care in rural settings. I think this is but one large step in the right direction toward reducing the disparities in access to the highest quality of care for our patients.”

Supporting hospitals across the region

High-quality perinatal care and labor and delivery services are synonymous with the ECU Health name. Dr. James deVente, associate professor at Brody and medical director of obstetrics at ECU Health Medical Center and Angela Still, senior administrator for women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center, have helped lead a perinatal outreach team that takes high quality training and best practices into other hospitals across the region, including facilities not affiliated with ECU Health.

Since 2012, the outreach team has visited every hospital across the region and has helped smaller hospitals better prepare for expectant mothers and new babies with serious medical conditions. From 2018-21 alone, the perinatal outreach team visited 18 different hospitals across the region, hosting 169 simulation days and educating more than 500 students on advanced life support training, emergency simulations, electronic fetal monitoring and more.

According to Dr. deVente, these efforts are a necessary part of improving care, reducing infant mortality and helping eastern North Carolina thrive.

“Data shows us that when a woman has to travel more than 50 miles to a hospital, her outcomes are worse. Data also shows us that businesses want to come to communities where labor and delivery services are present,” Dr. deVente said. “At ECU Health, we designed the outreach program and cover the cost of this work with those realities in-mind. If we are going to solve the infant mortality issues that our region faces, we are going to have to work together with health care partners across the East. I’m proud to say we are leading the way in that regard and the work is truly making a difference.”

Innovations to bridge gaps

It is no secret that eastern North Carolina is a vast rural region with long travel times between communities. An innovative program launched in 2020 at East Carolina University is helping to make women’s telemedicine, telepsychiatry and nutritional support services more accessible.

The MOTHeRs Project was first offered to patients at primary care obstetric clinics in Carteret County and has since expanded to ECU Health and other clinics in counties across the region. Through formalized partnerships with clinics, patients in the practices are cared for by both an ECU specialist and their local physician through a combination of telehealth and face-to-face visits.

Dr. Dwyer and Outer Banks Women’s Care were the third clinic in the ECU Health system to join the MOTHeRs Project. Maternal-fetal medicine and behavioral health care offerings for expectant mothers has been a much needed addition to the practice.

“We have identified access to mental health care as the greatest need in our rural communities. This need is increased during pregnancy and the post-partum period. Providing this service is a huge addition to maternal health care,” Dr. Dwyer said. “We have already begun to have mental health appointments in our office through the MOTHeRs Project. The feedback from our patients have all been very positive. This is just the beginning of learning how to give the needed specialized care in rural offices.”

Through its ongoing work, the MOTHeRS Project expects not only to provide care to those who need it, but also to generate new knowledge regarding how barriers to care can be better addressed. It aims to be a national model to ensure that every woman in rural America has a safe and healthy pregnancy and delivery.

“ECU Health, Brody and East Carolina University are truly pioneering high-quality rural obstetrics and women’s care services,” said Dr. Michael Waldrum, ECU Health CEO and dean of Brody. “Our hospitals and clinics provide excellent care in communities across eastern North Carolina. The perinatal outreach team trains other smaller hospitals on emergency care, best practices and more. Telemedicine innovations like the MOTHeRs Project makes patient-centered care more accessible. I’m proud of the work that all team members do to help our mothers, babies and communities thrive.”

Resources

In recognition of Veterans Day, ECU Health hosted a series of special events to recognize veterans from across the health system.

At each of the nine ECU Health hospitals, team members came together at 9:05 a.m. to recite the Pledge of Allegiance to honor the service and sacrifice of those who have served the country in the military.

The morning celebration at ECU Health Medical Center included a moment of silence and reflection as well as a role call for each branch of the military represented.

Mark Dunn, chief diversity, inclusion and talent management officer at ECU Health, shared his appreciation for veterans as the son of a U.S. Army veteran. He said hosting this event for the first time as ECU Health was a special opportunity to welcome new faces to a tradition at the hospital.

“We wanted to make sure we included our friends and family at the Brody School of Medicine,” Dunn said. “I wanted to give a special welcome to our Brody family as being part of ECU Health itself, as we continue to integrate and partner together. At one point we would have celebrated approximately 542 veterans from legacy Vidant, but as ECU Health today we celebrate approximately 1,400 veterans.”

The event gave special recognition to self-identified ECU Health veterans with a pamphlet listing their names.

Brian Floyd, president of ECU Health Medical Center and chief operating officer of ECU Health, offered a reflection and moment of gratitude for veterans and their families during the event — which is typically celebrated outside and near the United States flag that welcomes guests to the hospital — and today took place indoors due to inclement weather.

He said it is a special choice for our military veterans to continue to serve their country in health care, especially in a rural community.

“It’s so important to remember, it’s not just what you do in the military, but who you are in the military,” Floyd said. “That’s why we want to celebrate you today because what you choose to do is service, what you choose to do is honor other people, what you choose to do is sacrifice. At one point, that is military duty but you’re here in this organization because it carries through your life and you’re still serving and you’re still honoring and you’re still protecting.”

Transplant surgeon reflects on U.S. Army service

Dr. David Leeser, a transplant surgeon at ECU Health and a U.S. Army veteran, said he was raised to have a service heart.

When he was accepted into medical school, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Army.

“When I was in the Army, we had action in Afghanistan and Iraq,” Dr. Leeser said. “I ended up in Baghdad and it was during some of the surges and we took care of a lot of folks. It’s hard seeing young people in their late teens and early 20s injured in very profound ways that their lives will never be the same.”

Dr. Leeser said it was meaningful to him to be part of a team that helped send veterans back home to their families. He said his military experience is still something he carries with him today.

In gratitude

ECU Health would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to our veteran team members and all veterans for their service to our country.

It’s been sixteen years since Brent Carpenter’s life-changing injury.

“I dove into the pool with a shallow dive, hit the front of my head, and that knocked me out completely,” Carpenter said. “And I woke up on the surface where I couldn’t move any extremities.”

Paralyzed by the accident, the eastern North Carolina resident never gave up.

“The smallest little things can help you tremendously. So I have a saying that small steps are monumental gains,” Carpenter said.

Those small steps have served him well. Brent has since regained partial function of his hands and arms. He’s also tackled a massive personal goal, completing an annual charity event called “The Crossing” that takes place at Lake Gaston.

“The idea is that you’re crossing this part of the lake, which is give or take a mile, and however you want to – you can swim, you can kayak, you can float, paddle board, however you can get across,” Carpenter’s trainer, Susan Callis, said.

“A lot of people thought, ‘You are swimming this with a life-jacket, right?’ I was like, ‘Absolutely not.’ I wanted to do this just like everybody else was doing this and show people that anything’s possible,” Carpenter said.

Brent’s mindset and persistence served him well.

“We started out working on pool entry and exit,” said Callis, “and then working on water safety skills, working on breath control and lap swimming, holding his breath underwater.”

“It started as a half mile”, said Carpenter, “then I got three quarters there and then I got to the point where I was doing it consecutively during the week”.

It’s evidence-in-action that anything is possible with commitment, dedication and no shortage of cheerleaders.

“You do whatever you can to get across, first of all”, said Carpenter. “But I have always swam on my back when it comes to long distances. So when I came up to the finish line, I couldn’t see, you know, I didn’t have eyes in the back of my head. But when I turned around and Susan was right beside me like, you know, I heard the biggest applause I’ve had since playing sports when I was walking. To achieve a goal like that is, it’s priceless”.

It’s one impressive goal down with many more to follow.

“I think my goal each year is to make the world more accessible”, said Carpenter, “to not only my friends, but just people in my community that’s going through the struggle like me.”

Resources

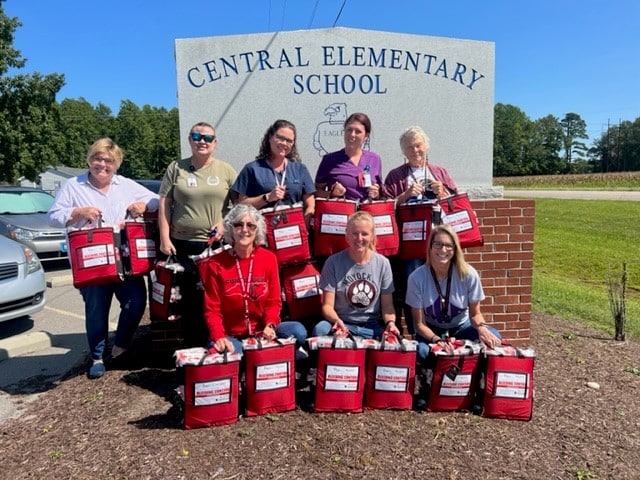

Greenville, N.C. – ECU Health donated Stop the Bleed Kits to public schools in Tyrrell, Currituck, Northampton and Halifax counties as part of its goal to distribute these life-saving resources to public schools across eastern North Carolina. These kits provide resources such as tourniquets, trauma dressing, compressed gauze, gloves and training for school staff in the case of a bleeding emergency before professional help arrives.

“ECU Health is excited to continue expanding our distribution of Stop the Bleed Kits in the counties we serve in eastern North Carolina,” said Erika Greene, pediatric trauma program manager for Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center. “Time is of the essence for traumatic injuries, and early intervention can save lives. In rural areas like eastern North Carolina where the distance between schools and hospitals may be greater, these kits enable school staff to treat children early, improving chances of better outcomes.”

Stop the Bleed Kits are funded by Children’s Miracle Network with training provided by Maynard Children’s Hospital. ECU Health has donated more than 64 Stop the Bleed Kits to schools this year, with a total of 354 kits in 12 counties since the program started in eastern North Carolina. School nurses in each county help train staff to use the kits, which ensures more children can be treated with supplies that do not expire.

“We are thankful for the generous gift of Stop the Bleed Kits provided by Maynard Children’s Hospital for every school in Currituck County,” said Jennifer Solley, school nurse, Currituck County Schools. “An emergency in the school setting can occur at any moment. Stop the Bleed training and equipment in each school will equip the staff with the knowledge and tools needed to respond to any bleeding emergency. With these kits, we are prepared and able to reduce or eliminate the loss of life due to an emergent bleeding situation whether it be a single playground injury or a mass injury situation.”

Preventable blood loss is one of the most common contributing factors in trauma-related deaths. Approximately 40 percent of trauma-related deaths worldwide can be attributed to bleeding or its consequence. If bleeding is managed early, the chances of recovery and survival are much greater. The items in the kits help control the loss of blood, leading to positive outcomes for those who sustain injuries.

Pediatric patients at the James and Connie Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center got a little taste of Halloween as they had the chance to dress up and see ECU Health team members and community groups participate in a parade.

During the parade, floats with team members dress up as everything from Disney’s Up characters to safari themes poured by while patients and families had an opportunity to step outside of their rooms and enjoy some fresh air on a warm afternoon.

Quionna Lofton, the mother of pediatric patient Emoni Salvant, said it was a great experience for her and her daughter.

“It makes me feel really good,” Lofton said. “I didn’t think she would get to experience Halloween today because we are here. This is very nice and well thought out, it was just very lovely.”

Emoni said her favorite float was the Trolls characters and her mother agreed, since she got to see her daughter’s smile light up as it came by.

Various community partners came out to bring a little joy to the youngest patients at ECU Health Medical Center. The Greenville Fire Department brought two trucks to the parade while the Pitt County Sherriff’s Office showed off a safari-themed float. The Down East Wood Ducks baseball team mascot, DEWD, gave patients a big wave from the back of a Jeep while ECU’s mascot, PeeDee the Pirate, interacted with patients and families.

Karolyn Martin, Miss North Carolina 2022, was on hand for the parade as well. She said it was a great experience, and a personally meaningful cause for her.

“My younger sister actually has Crohn’s Disease,” Martin said. “When she was diagnosed, she was in a hospital for about eight months of her year in 8th grade. I know how important it is for families to have people come that care about their children and also to celebrate the people that are making sure children are safe and healthy – that’s so important and why I was so excited to be here.”

Patients had the opportunity to select a costume from those available in the Maynard Children’s Hospital and got to select a party favor, including books and other fun activities.

Chloe Williams, a Child Life intern who helped organize the event, said it was special to see the smiles on the faces of patients and families after the time spent planning.

“I think it’s great. I think it provides a sense of normalization to the hospital experience, because a lot of the time they don’t get to have a Halloween if they’re here,” Williams said. “Just to provide something that they can enjoy and the parents can enjoy, too, is a really special thing.”

Williams said it’s also something team members look forward to each year. Whether they are dressing up and riding along on a float or out in the sea of children, it’s a welcomed opportunity to see patients in their natural setting – enjoying time as a kid.

With an audience of more than 90 Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University first-year medical students, leaders from ECU Health and Brody discussed the power of storytelling and narrative medicine during the 14th Annual Jose G. Albernaz Golden Apple Distinguished Lecture.

Narrative medicine is an increasingly popular technique that utilizes storytelling for health care providers to understand their patients as people and help process their own emotions around their work. At ECU Health, where compassionate care for patients and for the care team are foundations of how the organization meets its mission, the benefits of narrative medicine can make a difference in the clinical setting.

For first-year Brody students, the lecture provided an opportunity to learn about the value of narrative medicine so that they can apply it to their own education and future careers.

Dr. Christina Bowen, chief well-being officer of ECU Health, was once a first-year Brody student herself. In her opening remarks, she challenged students to take up narrative medicine early in their journey to becoming providers.

“The profession of medicine brings cases that will touch your hearts with much joy and sorrow. Write those stories down,” Dr. Bowen said. “These stories will be with you the rest of your medical career. Embracing the power and importance of these stories will support your emotional well-being and your growth into an excellent physician.”

Dr. Sharona Johnson, the nursing Advanced Clinical Practice administrator at ECU Health, served as the keynote speaker for the event. She said storytelling is key to understanding our humanity and helps leave a legacy for all people.

Dr. Johnson, who is a published author, is an advocate for narrative medicine – both to understand patients and as a well-being tool to get her own feelings down on paper.

“We’re learning that stories are important because we’re telling our stories,” Dr. Johnson said. “Physicians and health care professionals are writing books. We’re finding that our life has to have meaning. You can’t go through your life without thinking about, ‘Why am I here, what is the purpose, why is this patient sitting in front of me?’ It has to have meaning.”

Dr. Jason Higginson, chief health officer of ECU Health, said he received a written note from the first patient he gave a full clinical exam to in medical school. He said he can still picture himself in the exam room and remembers the patient frequently because of the heartfelt note the patient shared. He reflected that he wished he’d known more about narrative medicine as a young doctor so he could have captured more experiences like this from early in his career.

The relationship between ECU Health and Brody is important for many reasons. The opportunity for experienced providers to share valuable lessons with medical students in a clinical setting is one of the special benefits. Dr. Michael Waldrum, CEO of ECU Health and dean of the Brody School of Medicine, said the teaching offered at Brody and ECU Health stretches beyond the walls of the classroom.

“This was a really important lesson today for students and a great reminder for anyone already in health care,” Dr. Waldrum said. “Narrative medicine and storytelling help in many aspects. Brody School of Medicine concentrates on producing physicians that actually understand humanity. I’m really proud of that.”

Dr. Waldrum said that understanding humanity and human interaction is what led him to being a pre-med English major as an undergraduate.

Learning the humanities, he said, helped lay a foundation for him as a person and care provider. The lessons learned as an English major were reinforced in his first clinical rotation during his third year of medical school when a mentor told him to learn something from each patient, whether it is a personal or medical fact. He said that stuck with him and taking it into action paid off.

“That’s the story of humanity and history, understanding and respecting differences,” Dr. Waldrum said. “Stories are about history and looking backwards, but it’s also about creating an optimistic and positive future. That’s what we’re doing here: creating a new health system, evolving our school of medicine, always changing and making sure that we meet our communities needs and that we educate the best humans on the planet.”

The Albernaz Golden Apple Distinguished Lecture series is a great example of how ECU Health and the Brody School of Medicine collaborate to bring excellence in the clinical and academic setting for the betterment of eastern North Carolina.

Dr. Sy Atezaz Saeed

Contrary to popular belief, psychiatric disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are just as common as other chronic conditions. About 11 percent of the U.S. population has been diagnosed with Diabetes, while in comparison 26 percent of the population has a diagnosable mental disorder per year.

Unlike other chronic conditions, there are few resources to treat mental illnesses in North Carolina, which is exemplified by the lack of behavioral health providers. Alarmingly, 42 out of 100 counties in the state have no psychiatrist or active behavioral health provider, leaving more than half of adults with mental illness without treatment options.

How did we get here?

In 2001, the state of North Carolina began to privatize mental health services by transitioning them from public area authorities to private provider groups. This transition meant private agencies would become solely responsible for caring for people with behavioral and mental health disorders as well as substance use disorders. For those without access to a local behavioral health professional or without the ability to pay for care, their only option is often the hospital emergency department (ED). In fact, one out of every eight ED visits is related to mental illness or substance use disorders. This puts more strain on EDs, which were not designed for this type of specialized care.

Working together

As a community, we need to work together to change the way behavioral health care is delivered in North Carolina. Solving the mental health crisis requires collaboration and partnership across a broad spectrum of services. One way ECU Health is doing this is through a joint venture partnership with Acadia Healthcare, a national leader in providing behavioral health services. Recently, we announced plans to build a state-of-the-art behavioral health hospital that is slated to open in spring 2025, pending regulatory approval.

In addition to serving adult patients, the new hospital will provide much-needed access to the behavioral health needs of children and adolescents, providing the only child and adolescent psychiatric beds within 75 miles of Greenville. Together, both ECU Health and Acadia will invest more than $60 million in expanding behavioral health resources.

Working in tandem with other partner organizations as a network providing a wide variety of treatment options can create a much greater impact than we’re able to on our own.

Everyone deserves access to high-quality health care, and ECU Health is committed to doing its part to offer vital behavioral health treatment to eastern North Carolina. While this partnership provides promise for those who are seeking behavioral health care, my hope is that we continue to find ways to partner in our communities and across the state to ensure our residents have access to the care they need to live healthy, fulfilling lives.

Sy Atezaz Saeed, MD, MS, FACPsych is Executive Director of the Behavioral Health Service Line for ECU Health, and Professor and Chair Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University. He also serves as the Founding Director of the Center for Telepsychiatry at ECU and as the Founding Director of North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program (NC-STeP). Dr. Saeed has published more than 100 peer reviewed publications. In 2019, he was awarded the prestigious Gov. Oliver Max Gardner Award, the highest UNC award and selected by the UNC Board of Governors, which recognizes UNC system faculty who have “made the greatest contribution to the welfare of the human race.” To learn more, visit ENCBehavioralHealth.org.