The Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center is celebrating its 10th year of offering high-quality, compassionate care in a soothing environment for patients and families in eastern North Carolina.

Dr. Matthew Ledoux, pediatrician in chief at Maynard Children’s Hospital, said the children’s hospital has immensely benefited the youngest patients in the East and made for more seamless care.

“The children’s hospital itself has given us the opportunity to grow services – we started an ECMO program, we’ve started and developed a dedicated Children’s Transport Team that flies all over the region and picks up kids and brings them back here,” Dr. Ledoux said. “The fact that we have all the subspecialty care, we have all the surgical care and generalized pediatric care here makes all the difference. It’s really a shining light in the East.”

Over the past 10 years, countless improvements have been made that have positively impacted the lives of many children and their families in eastern North Carolina. Other key expansions included the Pediatric Day Medical Unit, Pediatric Radiology Unit, and Pediatric Pharmacy among several other additions.

Kim Crickmore, PhD, RN, senior vice president for Women’s and Children’s Hospital and Community Health Programs, said the Maynard Children’s Hospital is an integral part of health care in eastern North Carolina today. Over the last 10 years, the children’s hospital has delivered more than 37,000 babies, with more 61,000 inpatient admissions, 216,000 emergency cases, 223,000 outpatient cases and an additional 700,000 pediatric outpatient visits through the ECU pediatric outpatient center.

Kim Crickmore, PhD, RN, senior vice president for Women’s and Children’s Hospital and Community Health Programs, said the Maynard Children’s Hospital is an integral part of health care in eastern North Carolina today. Over the last 10 years, the children’s hospital has delivered more than 37,000 babies, with more 61,000 inpatient admissions, 216,000 emergency cases, 223,000 outpatient cases and an additional 700,000 pediatric outpatient visits through the ECU pediatric outpatient center.

“When we consider the impact to the region over the last 10 years, it’s really unbelievable,” Crickmore said. “It means so much to us here at the hospital that we’ve been able to provide care, primarily under one roof and unite all the services and to be the destination in eastern North Carolina for children who are sick or injured and need the specialty care we provide.”

Crickmore and Dr. Ledoux both said one of the services they are most proud of is the Children’s Transport team. The team consists of intensive-care trained nurses and respiratory therapists skilled in providing the specialty care many children need from the onset of transport to arrival at Maynard Children’s Hospital. Crickmore said it has been an intentional focus to build the program over the last five years and the program has seen many successes.

The Space

The amenities offered in the under-the-sea-themed Maynard Children’s Hospital are designed with patients and families in mind. Soothing young patients in a health care setting is no small task, but the children’s hospital is uniquely equipped to handle the challenge.

Dr. Ledoux said the community has stepped up time and again to provide resources and make donations that make a real difference for patients and families.

When thinking about his favorite area of the Maynard Children’s Hospital, Dr. Ledoux came back to the light tower, which can be seen when driving past the hospital. He said it’s a reminder of why he, and every children’s hospital team member, shows up to work every morning – to take care of the youngest patients in eastern North Carolina. He said he’s often asked what the colors on the light tower mean when people drive by at night.

“The reason is, we’re generally celebrating a child, we’re celebrating the end of a treatment, they’ve finished chemotherapy, or maybe they’ve been in the NICU for two or three months and they’re getting to go home,” Dr. Ledoux said. “We really try to make sure that the families and children get to pick the color and the time, but any time you see the color change anything different from our usual light blue, we’re celebrating a child and a family so it’s pretty exciting.”

Into the Future

Crickmore and Dr. Ledoux both said the next 10 years are something they’re looking forward to with the Maynard Children’s Hospital. They hope to continue expanding services and looking more to the region to bring specialty care closer to home for patients and families.

Dr. Ledoux said he and other physicians in the system have enjoyed their time spent in the region and the ability to help patients and bring key services closer to home for patients makes it special.

“I think the biggest thing is the distance that people have to travel,” Dr. Ledoux said. “We know that it’s a very underserved population and there’s a lot of poverty. People have challenges paying for gas or even having a car. The closer we can be to them to provide those services, the better.”

Another upcoming project that will impact pediatric patients in the East is the behavioral health hospital, slated to open in Greenville in 2025. ECU Health is partnering with Acadia Healthcare to build the state-of-the-art facility that will feature 24 inpatient beds specifically for children and adolescents with mental health needs. These beds will be the first of their kind in ECU Health’s 29-county service area and the only child and adolescent beds within 75 miles of Greenville, North Carolina.

Join us in celebrating the Maynard Children’s Hospital and all of its team members for the last 10 years of service to eastern North Carolina.

For more than 25 years, the Pediatric Asthma Program at the Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center has worked to help patients and families living with asthma lead healthy lives.

Jeanine Sharpe, social work care manager for the Pediatric Asthma Program, said the goal of the program has always been to decrease emergency department visits, reduce school absences due to asthma, provide education and improve quality of life for patients and families.

“Currently, there are about 5.1 million children under the age of 18 that have asthma in the U.S. and it’s the leading chronic disease for children,” Sharpe said. “Just for our service area last year, we had 1,687 pediatric asthma patient referrals. It’s the number one reason for school absences and the number two reason for hospital admissions for children. But we know that asthma is a controllable disease. What we find is that a lot of times the missing piece is just education.”

Sharpe said the program has touched many families over the years, whether it’s just one interaction or years of working on a family’s case. One family that has seen the impact of the program recently is the Carr family.

Dalton Carr III was diagnosed with asthma three years ago and struggled with wheezing, coughing and attacks in the years since.

Dalton III’s mother, Shanika said she was scared when her son was first diagnosed and she wasn’t sure how to handle certain situations. This past December, Dalton had an incident and was seen in the emergency department for his asthma.

“That’s when I met Ms. Sharpe,” Shanika said. “I was confused at the time, but ever since I met Ms. Sharpe, it’s been easier to learn things. I was confused with the things different doctors were telling me and I really didn’t understand how serious it was.”

Dalton III’s father, Dalton Jr., said it has been a great experience working with Sharpe and the Pediatric Asthma Program team.

He said the education and support offered have helped their son be confident and join in the everyday activities of other children his age. While he used to struggle, today he does not wheeze, cough or have flare ups from his asthma. Dalton Jr. credited the work with the Pediatric Asthma Program for this turnaround.

“She got us in a good routine for him. Ever since we’ve gotten Dalton on a consistent routine, he hasn’t had any problems,” Dalton Jr. said. “It’s even to the point where he can tell us when he needs his pump. He might say, ‘Mom or dad, I need my pump’ or ‘I’m good.’ He plays football and he’s running and tackling and it’s a lot but with Ms. Sharpe being in our lives these last few months, it’s just helped a lot.”

Dalton Jr. encouraged families to reach out for help and to learn what might work best for their child’s asthma.

Malorie Whitaker, respiratory care manager at ECU Health Medical Center, said the program is designed to help patients from one to 18 years of age feel more comfortable while they manage their asthma and participate in normal childhood activities.

She also said the program is set up to meet children where they are and eliminate barriers to care.

“Sometimes they’ll come into our office to do different testing or do some education, but usually we meet them,” Whitaker said. “So we’ll get into the homes, we’ll go into the schools, into the clinic, wherever they are. Some of these kids that we see don’t have transportation or transportation is difficult for them, so that’s why we like to go into the school or into the homes to help them.”

To learn more, or to speak with someone close to you, visit the Pediatric Asthma page or call one of the ECU Health locations offering pediatric asthma services.

- ECU Health Bertie Hospital: 252-833-2861

- ECU Health Chowan Hospital: 252-833-2861

- ECU Health Edgecombe Hospital: 252-641-7382

- ECU Health Medical Center: 252-847-6835

- ECU Health Roanoke-Chowan Hospital: 252-209-3117

By ECU News Services and ECU Health News

Getting through medical school can be tough – long hours, books and tests, and more books. However, in between classes and all-nighters, two students from the Brody School of Medicine have established a flourishing volunteer program to bring doula-like services to a region of North Carolina starved for birthing support.

The birthing companion program was started in October 2022 by Uma Gaddamanugu and Shantell McLaggan, both second-year Brody students and Schweitzer fellows. The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship supports graduate health professionals drawn from across the state who learn and work to address unmet health care needs in North Carolina.

Gaddamanugu’s and McLaggan’s fellowship project is focused on improving birth experiences of high-risk pregnant mothers in eastern North Carolina through the free birth support program to add an extra layer of support for women in the birthing process.

Patient populations in rural parts of eastern North Carolina simply need more help, Winston-Salem native Gaddamanugu said, from prenatal care through the laboring process, and certified doulas are an expensive out-of-pocket resource for which most North Carolinians must pay out of pocket because health insurance often doesn’t cover the cost.

“We are the only hospital with a high-risk labor and delivery unit for half the state. You think about how far some of these people have to travel, which makes it way harder for their support people to come with them,” Gaddamanugu said.

In February 2022, the North Carolina Institute of Medicine reported that the state’s maternal mortality rate was 27.6 per 100,000 births, which is slightly lower than the national average, but more than double the previous year’s rate of 12.1 per 100,000 births.

A 2021 study by the North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Committee reported that 60 women died from pregnancy related causes from 2014-2016. Of those, nearly 60% were from minority racial categories and more than one in three were from rural areas. What’s more troubling – the study determined that 70% of maternal deaths could have been prevented by changing “patient, family, provider, facility, system and/or community factors.”

The program

At first, the program had 18 volunteers, but since its inception in October 2022 the ranks of birthing support volunteers have doubled to 37. At the beginning of February, the volunteers had assisted with more than 70 births, which is “way past our goal that we had initially set,” Gaddamanugu said.

Volunteers from the program come from a wide range of backgrounds, though most are medical or nursing students. Some are undergraduate students from main campus who want to be part of a program that serves the community. For now, the program is staffed almost completely by ECU students, though Gaddamanugu and McLaggan will soon hand the program’s day-to-day management off to first-year medical students who aim to open the program up to the public.

“Our program is very much modeled off a program at UNC. They’ve been doing that for about 20 years,” Gaddamanugu said. “A Wake Forest medical student started a similar volunteer doula program two years ago through the Schwitzer Fellowship. It’s just neat to see that it was possible with the structure of the organization to bring that program here, because there’s a whole different need in eastern North Carolina.”

Gaddamanugu stressed that the volunteers in the program, who support the labor and delivery services at ECU Health, aren’t certified doulas but rather are there to help during the immediate labor process. For one delivery, that might be a non-clinical, non-medical role – a friendly face and a hand to hold – and in other cases it might be running through the hospital to find a phone charging cable so a mother can stay in contact with her other children at home.

Leslie Coggins, a charge nurse on the labor and delivery unit at ECU Health Medical Center in Greenville, said the volunteer program has been a great success, both for the mothers in the delivery process as well as for students on track to become the next generation of health care providers.

“We’ve always had a great relationship with our residents, but now we have almost a pipeline — doctors, potential doctors, nurses, someone interested in birth and supporting birth in its natural function,” Coggins said. “To share that experience with up-and-coming providers and nurses who will be taking our places someday is huge.”

While the volunteer program is currently staffed by students, the student organizers and Coggins as the nurse manager of the labor and delivery unit hope to soon include members of the public. Those interested in volunteering should contact the program by emailing [email protected].

Training medical professionals

The ECU version of a volunteer birth companion program is rooted in experiences both medical students had working as volunteers in hospitals in doula-like roles. Gaddamanugu volunteered during her time as an undergraduate at UNC; McLaggan, who is from Thomasville, spent several years after her undergraduate education working at the Cherokee Indian Hospital in western North Carolina and helped establish a volunteer doula program there.

Both students are interested in pursuing a career in obstetrics.

McLaggan’s mother told her from an early age that she was smart enough to be a doctor. After researching the requirements and being captivated by the science of medicine, she fell in love with the idea.

“I feel like I have the mental, emotional and the physical capacity to do something as strenuous as being a doctor,” McLaggan said. “Because I have those qualities, I feel like it’s my obligation to become a doctor and serve people to the maximum of my abilities.”

Medicine was also a calling for Gaddamanugu, who said that the challenge is humbling but she sees a future where she can make a difference by “maternal and child health disparities in our community” which fit the impact that she hopes to make in the world.

She said that the experiences at the bedside have colored the conversations that she has with her medical school peers about the experience of medicine from the patient’s perspective.

“We know birth is hard, but here is what it really can look like,” Gaddamanugu said. “The U.S. has an awful maternal mortality crisis, and we can hear those numbers all day long in school, but the numbers don’t mean anything until you see it in person, and you realize some of these patients are extremely sick.”

For Dr. Kerianne Crockett, ECU Health OB/GYN and Brody clinical assistant professor, the program has clear benefits for the patients she serves. She has heard from patients who appreciated having another source of support during their delivery.

“Delivering a baby is one of the most exhausting, exhilarating, sometimes scary experiences of a patient’s life,” Crockett said. “There is good evidence that patients with a continuous support person present throughout labor — whether that person is a family member, a spouse or a doula — have better birth outcomes, including lower rates of cesarean delivery. I am so proud that our bright, compassionate, empathetic medical students are now able to be that continuous support person for all kinds of patients, including those who otherwise would not have had anyone besides the medical team there for their delivery.”

Student involvement in health care delivery, and the unique perspectives students offer patients, is a hallmark of a large academic health system like ECU Health. As students learn from the clinical experience of providers at ECU Health, they are empowered to innovate and bring ideas to the table that lead to better patient experiences and brighter outcomes.

“As an academic health system, our medical students help to enrich the patient experience with their energy and ideas,” said Angela Still, senior administrator of women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center. “The birthing support volunteer initiative is a great example of how Brody students go beyond the walls of the classroom and make a direct impact on the patients we’re proud to serve.”

Serving eastern North Carolina

Sometimes the most important support that a birthing companion can provide comes from skills that can’t be taught in a formal doula class.

McLaggan remembers one time she volunteered with a woman who had a number of kids already — the most recent born by C-section. The medical staff recommended another C-section, which the woman was reluctant to agree to due to the complications she had with the previous birth. The challenge that McLaggan was able to help resolve wasn’t convincing the woman to have a C-section, but rather just communicating with her at all. The woman was Haitian and spoke Haitian Creole and little English.

“I happened to speak French, which is very similar to Haitian Creole, so she was able to communicate to me, where she was coming from and what her needs were,” McLaggan remembered. “I was able to bridge that gap and she ended up delivering naturally. I felt so honored and privileged to have been in the room.”

Another of the volunteers in the program has similar experiences with language gaps being a hindrance to quality health care. An undergraduate student recounted to Gaddamanugu how, growing up in eastern North Carolina, she was always saddled with translating for her mother and siblings during medical appointments — a task that shouldn’t really be shouldered by a young person. The student volunteer said, though tears, that she was so grateful to be able to translate for delivering mothers because she knew first-hand the constricting fear and anxiety of being language-locked in a stressful medical situation.

While the language capabilities that some students bring to the hospital bedside are important, Coggins said, patient populations in eastern North Carolina are getting sicker, which often requires the health care team members to devote their attention to the physiological status of the patient.

“We try to promote natural delivery as much as we can,” Coggins said, but sometimes the medical conditions of the mother and baby require doctors and nurses to focus on the immediate illness. “One-on-one support is essential with our patients. A lot of times our sick population are not from around here and don’t have the support system in place, so this is an added benefit so our nurses can focus on what is medically happening and where we need intervene.”

Gaddamaugu is awed at the privilege of being present at a birth.

“I’ve cried every single time; it’s one or two single tears, but they were C-section babies and you could sense the relief in the OR the moment the baby comes out safe and healthy,” Gaddamaugu said.

McLaggan has known that being in the room during the birthing process is what she has wanted to do since before kindergarten. She’s seen a handful of births as a volunteer and continues to be amazed by each one.

“Words don’t describe how amazing childbirth really is. I get so overwhelmed with emotion when I see 37 to 40 weeks of work and love going into this child that is coming into the world,” McLaggan said.

Resources

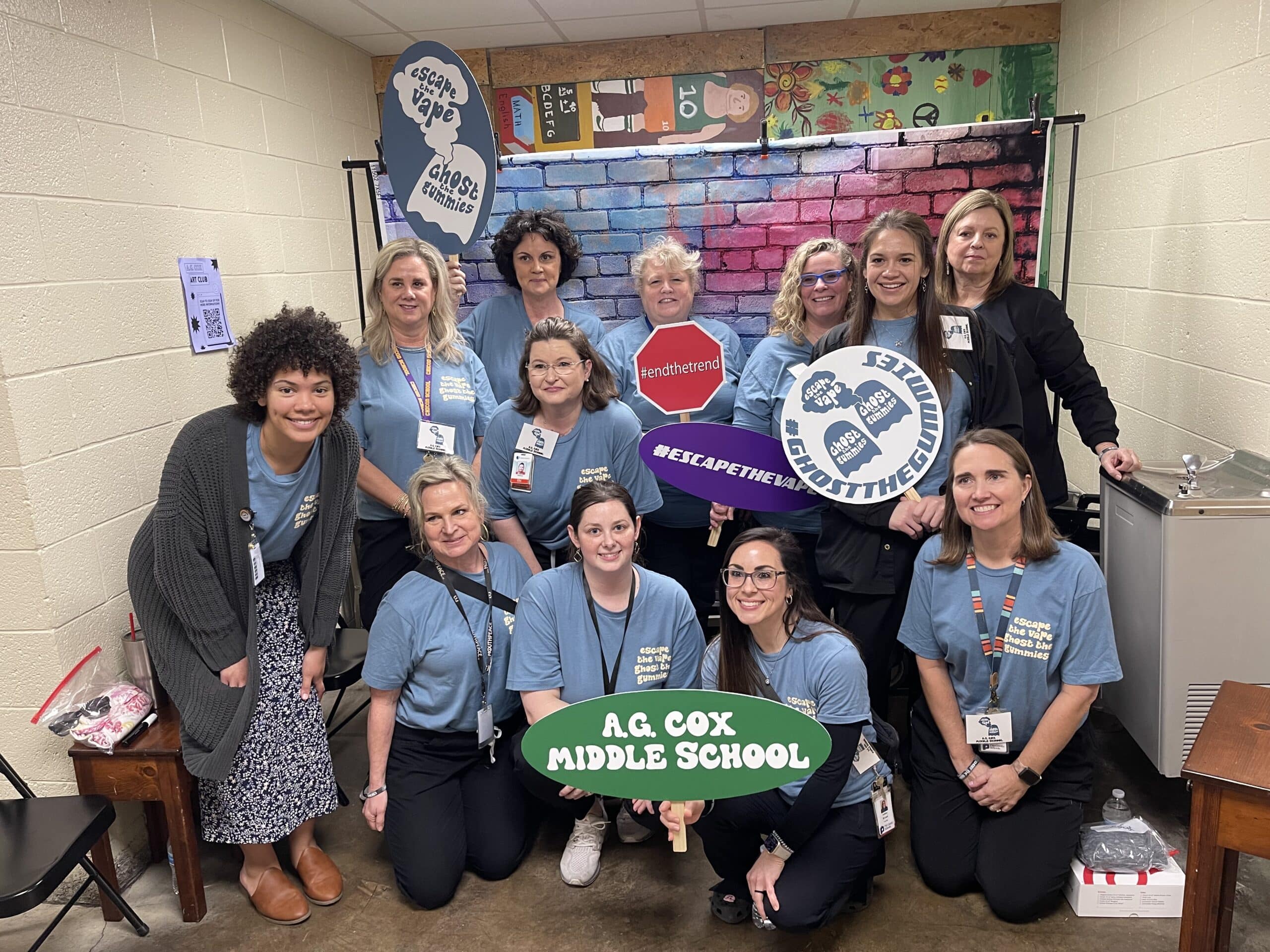

Students at A.G. Cox Middle School in Winterville learned about the dangers of vaping tobacco or other substances and drug use during an event hosted at the school on Feb. 28.

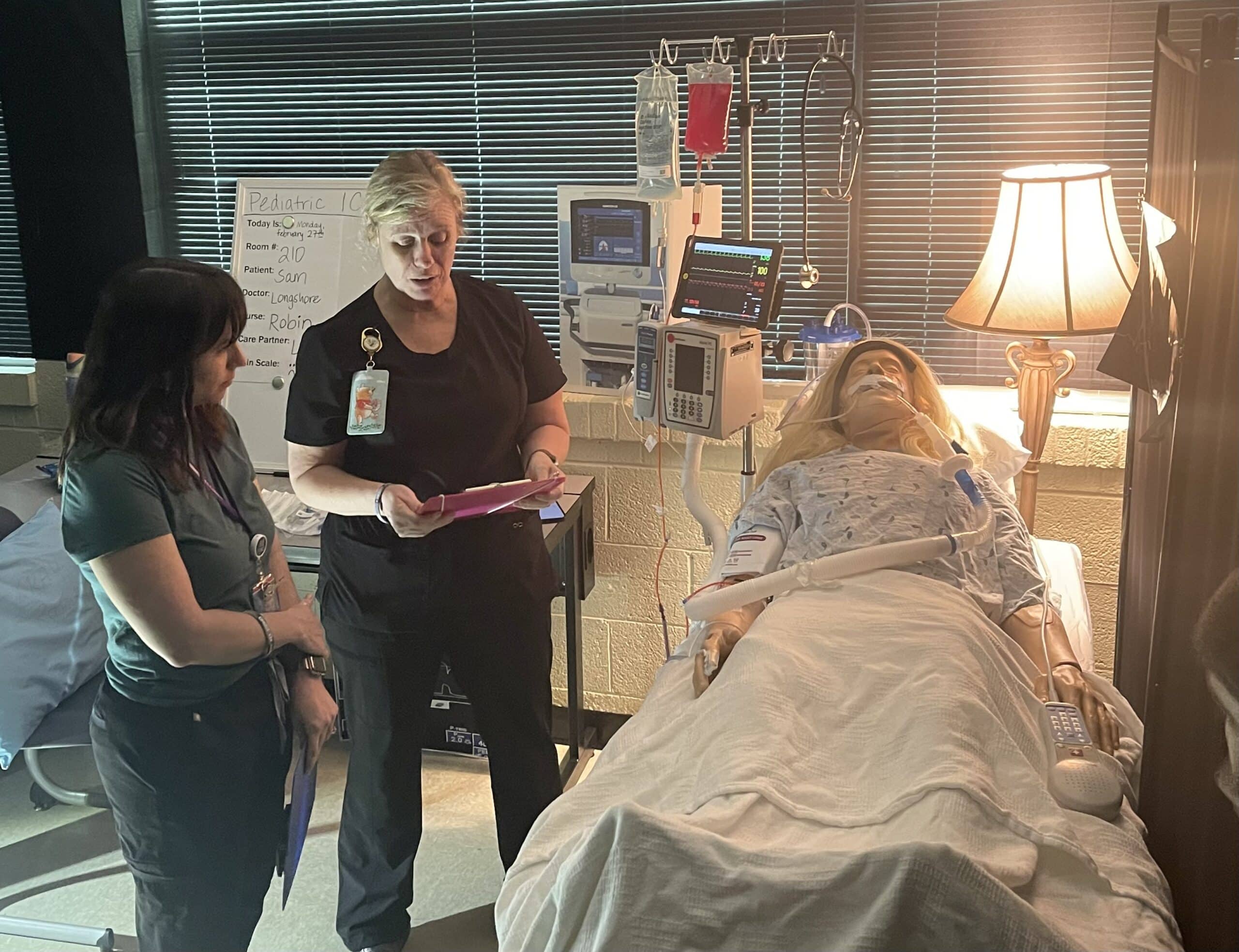

Pitt County School nurses, ECU Health team members and volunteers, and local high school students acted out two different scenarios for the A.G. Cox students, who are in grades 6-8, to show how quickly things can go wrong.

In one scenario, a student at a party takes a gummy from a friend, which turns out to be laced with drugs. The student then falls critically ill from the effects of the drugs.

In another, a student is taken to the hospital after using a vape they were told did not have tobacco in it, but instead was filled with an unknown drug.

Emerson Fipps, a senior at South Central High School in Winterville, helped act out the first scenario with another student and an ECU Health volunteer. She said she’s proud to support events where she can help other young people set themselves up to make positive decisions.

“Middle school is really where everything starts to come up,” Fipps said. “Teenagers are just trying to find themselves so they’re getting into things that they shouldn’t. They’re not really fully educated about everything these destructive decisions could affect. It’s really good for them to start hearing about it young because when they’re in these situations, they’ll already have the information.”

Tiffany Thigpen, the Region 10 tobacco prevention and control coordinator for the Pitt County Health Department, said schools across the country are seeing an increase of students vaping and using gummies and other drug-infused edibles.

The National Poison Data System reported 3,054 cases of pediatric edible cannabis consumption in 2021, a large increase from 207 cases in 2017.

Thigpen said one of the most important things parents can do to keep their children safe from tobacco and drugs is talk to them.

“Talk to your children, let them know that these things are not safe,” Thigpen said. “Let them know that it is OK to say no. Talk to them about refusal skills and ways to say no to their peers. Let them know they can talk to you about what they’re experiencing. If they do use these products, share the dangers with them and ways to stop.”

Thigpen said the county is working to get as much information as they can into the hands of students about the dangers of drugs and vaping to help stop addictions before they begin.

Laurie Reed, manager of school health services at ECU Health, said partnerships make all the difference for events like the one hosted at A.G. Cox Middle School.

“Our school board and our school health advisory committee are very supportive of programs like this in our school system,” Reed said. “We just hope we’ll be able to offer more of them. It’s a great collaborative effort and it takes a lot of effort on the part of our school nurses, Injury Prevention, our health department, but it’s a great collaborative opportunity for our community.”

The holiday season brings so much joy, especially for young children and their families that get to see them light up as they unwrap presents.

While picking out toys that young ones will love, it is also important to consider the safety of the toy, Ellen Walston, Injury Prevention Program coordinator at ECU Health Medical Center, said.

In 2021, there were more than 152,000 toy-related, emergency department-treated injuries to children under the age of 15, according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

“I think the thing is, because of COVID and supply chain issues, a lot of parents have a lot of pressure on that perfect gift,” Walston said. “But you don’t need to sacrifice safety.”

Walston noted toys with many pieces and stuffed animals with poorly sewn features as choking hazards for small children. A good test, she said, would be to use a toilet tissue roll to see what kinds of items might be a choking hazard for a child. If it could get stuck in a toilet tissue roll, it could be ingested and become a choking hazard.

She said often older children and younger children in the same home can play with different toys that may be safer for the older child than the younger child. It is important to remind older children to put away toys when they are done using them to make sure younger children cannot get hurt using that toy or ingesting pieces.

A key concern each year, though, is button batteries, Walston said. Button batteries can be found in many objects around a home, including car key fobs, thermometers, scales and some remotes. These can also be found in books that play music and many singing cards. Walston said if a child gets to these batteries, it can be very dangerous — not only as a choking hazard, but also the possibility for chemical burns from the battery.

Last, Walston reminded anyone purchasing a bike for a child to not forget a helmet and bell or another item that makes noise.

Walston said it all comes down to making educated choices and supervising young children while they play to keep them safe and avoiding an emergency.

“Please make sure that you’re paying attention to labels,” Walston said. “If a toy says ‘not recommended for a child under three years of age,’ you have to take those warnings seriously. Also, supervision is critical and just making sure that children are safe when they’re playing.”

Keeping children safe with their toys helps ensure a happy holiday season for all.

Resources

Learning your child is sick is devastating, in any language.

“He got sick when he was two years old,” Miguel Morales’ mother, Maria Martinez, said in Spanish. “His diagnosis was spelled LCH. It is one of the somewhat aggressive cancers. It was a very, very difficult process for him. Very painful for all of us to see my son suffer every day without being able to understand why he does not speak much.”

LCH, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is a rare form of cancer that most commonly appears in toddlers and children.

Complicating the diagnosis — the fact that English is a second language for Miguel, his mother Maria and their family.

“We take care of our patients that have are limited English speakers,” said Tania Elguezabal Christensen, Interpreter Services manager at ECU Health. “So we help them to navigate our health care system and we help them communicate with our providers, with our doctors and nurses about their health care.”

Tania and the Language Access Services team — which is comprised of interpreters and translators — help bridge an important gap for patients and families during a hospital stay. An integral part of a patient’s care team, they offer services for 240 languages and dialects across the ECU Health system.

“When we go to get medical treatment, we all want to understand what our diagnosis is and what the treatments are,” Elguezabal Christensen said. “When people don’t speak the language, it’s hard to understand all of that. That’s why it’s so important for us to be a conduit between patients and providers.”

Martinez said she was grateful for the assistance the Language Access Services team provided while her family navigated a challenging time.

“It was a very good thing for me,” Martinez said. “They have been very supportive during this long process with my son. They have helped me to better understand his situation, how to properly give the medications, and to clarify many doubts that I had with the doctors. Since I do not speak the language, they have been a very important source of support for me.”

One part of the journey that is easy to understand in any language, the milestone moment Miguel got to ring the bell at the James and Connie Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center. It’s a celebration of beating cancer, surrounded by the many teams who helped him along the way.

“For me it meant life, it meant opportunity, it meant opportunity to have my son with me,” Martinez said. “It meant everything. It meant that some of my worries about losing him were fading away. It meant that I could see him grow.”

Today, Miguel is a happy, typical 4-year-old boy. He loves to play and jump around, which was difficult for him to do while he was sick.

Martinez is grateful for the outcome — and for those who made it possible.

“Well, I thank everything, first to God and for giving us the opportunity to heal my son, to the entire doctor’s team, from interpreters, nurses, doctors, everyone who was there, the whole team because they really helped us a lot,” Martinez said.

Along with sharing her appreciation for her healthy son, Martinez also wants other parents to learn from her family’s experience.

“More what I would like to say is just my experience as a mother,” Martinez said. “I would tell people that are out there listening to me and mothers out there — ask questions. If someone tells you this is just an infection, keep digging and keep asking questions.”

Resources

The third Thursday of November is National Rural Health Day and ECU Health and the Brody School of Medicine are celebrating team members, faculty, staff and students by shining a light on the work they do to make a positive difference in the lives of the 1.4 million people living in eastern North Carolina.

A note from ECU Health CEO and Brody Dean Dr. Michael Waldrum: National Rural Health Day is a day to shine a light on the contributions of rural health professionals across the country. We created ECU Health earlier this year with high-quality rural health care in mind. The team members who work here truly personify the region and we wanted our name and logo to reflect that. We wanted our patients to know that the care we provide is backed by the educational excellence taking place at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University. More than anything else, we wanted eastern North Carolina to know that ECU Health will always represent them. That’s a testament to the more than 13,500 ECU Health and Brody team members, who embody our mission and serve our communities. Thank you for your service and commitment to our organization, region and patients.

ECU Health serves a vast rural region made up of 29 counties and home to more than 1.4 million people. Like many rural regions, people across eastern North Carolina face a number of systemic socioeconomic challenges which have negative impacts on health outcomes. Perhaps most tragic of all, the region has wrestled for years with higher infant death rates than the state average, driven by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, barriers in access to care and fewer local resources to support expecting mothers.

Dr. Madhu Parmar, an OB-GYN for ECU Health, practices in Ahoskie. She helps facilitate countless healthy deliveries, but the ones that don’t go as planned stick with her the most. That is because many of the complications are preventable, and adequate access to perinatal care helps facilitate positive outcomes for both mother and baby. The unfortunate reality is that rural and underserved communities simply lack access to the perinatal care they need.

“This issue is very personal because I feel like there are not enough resources, people and attention placed on caring for mothers and babies in rural areas,” Dr. Parmar said. “I feel like rural mothers and babies are the ones that need care the most and we must do all we can to ensure they have access to that care. You hear about smaller hospitals closing down their OB units and that just increases the risk to mother and baby. If a community has access to these services, you see how the mother and the baby can thrive. That’s what we’re aiming for at ECU Health, access for all.”

Dr. Parmar says the primary challenges she sees in her patients stem from poverty. Data tells us that 1 in 4 mothers in eastern North Carolina live below the poverty line and 1 in 8 are uninsured.

“Because of poverty, patients are not as healthy,” she said. “Obesity and chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, are the things presenting difficult challenges for normal patients, and those conditions are even more challenging for pregnant patients. The reality is that we take care of a lot of high-risk patients in the East because many of our patients experience poverty.”

Across the region, more than 50 percent of the mothers delivering babies at ECU Health hospitals are clinically overweight. In Ahoskie, where Dr. Parmar practices, the average Body Mass Index (BMI) is about 40, nearly 15 points higher than the high range of a healthy person.

Keeping patients informed and educated about their health has been a key focus, Dr. Parmar said. Understanding illnesses and what to watch for is half the battle; a healthy mom often times leads to a healthier pregnancy.

“A nurse who specializes in diabetes care comes to our office once a week to educate our patients,” Dr. Parmar said. “She teaches them how to monitor their blood sugar and how to improve their diet so that we have optimal outcomes for the babies. She works with our nurses, too, and makes sure they’re looking through patients’ blood sugar diaries when they come in. The biggest thing we can do is be available to these patients.”

Women’s care close to home

At a time when many rural communities across the United States are losing access to obstetrics and women’s care services, ECU Health is doing its part to maintain and enhance obstetrics offerings in hospitals across the region.

According to the Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 183 rural hospitals have completely shuttered operations since 2005. When a hospital closes in a rural community, it makes it difficult for that community to thrive. One of the initial signs of trouble for an ailing rural hospital is a reduction or elimination of labor and delivery services.

Women’s services closures are often driven by the sustainability of the service itself. Staffing an around-the-clock unit is difficult due to the shortage of health care workers. The absence of nearby maternity services results in longer travel times, higher costs and medical complications.

In 2019, an average of 47 babies were born per day across the 29 eastern North Carolina counties. Those babies represent the future of the communities in which they are born and live, signifying the importance of maintain hospital-based obstetrics and labor and delivery services.

Dr. Daniel Dwyer, an OB-GYN at Outer Banks Women’s Care, said he remembers a time when many mothers in the area used to deliver babies on the way to the hospital. He said having rural hospitals close to where patients are can make the difference for positive outcomes, especially for mothers and babies.

For those living in communities where specialist care may not necessarily be only a few miles away, it is important to find ways to bring services directly to them. At the Outer Banks Women’s Care clinic, Dr. Dwyer said the services they offer keep patients close to home while receiving leading-edge care.

“We have begun to see patients for perinatology consultations, which is an important part of coordinating care for our highest risk patients.” Dr. Dwyer said. “Historically, it would take more than a half day for patients to get a consultation with a maternal-fetal specialist. In addition to the travel, the setting and staff would be unfamiliar for the patient. There is increased anxiety, cost and potential for loss of key information when patients travel for services that can be delivered in their trusted medical home. We hope to continue to leverage the technology and professional relationships to provide specialist care in rural settings. I think this is but one large step in the right direction toward reducing the disparities in access to the highest quality of care for our patients.”

Supporting hospitals across the region

High-quality perinatal care and labor and delivery services are synonymous with the ECU Health name. Dr. James deVente, associate professor at Brody and medical director of obstetrics at ECU Health Medical Center and Angela Still, senior administrator for women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center, have helped lead a perinatal outreach team that takes high quality training and best practices into other hospitals across the region, including facilities not affiliated with ECU Health.

Since 2012, the outreach team has visited every hospital across the region and has helped smaller hospitals better prepare for expectant mothers and new babies with serious medical conditions. From 2018-21 alone, the perinatal outreach team visited 18 different hospitals across the region, hosting 169 simulation days and educating more than 500 students on advanced life support training, emergency simulations, electronic fetal monitoring and more.

According to Dr. deVente, these efforts are a necessary part of improving care, reducing infant mortality and helping eastern North Carolina thrive.

“Data shows us that when a woman has to travel more than 50 miles to a hospital, her outcomes are worse. Data also shows us that businesses want to come to communities where labor and delivery services are present,” Dr. deVente said. “At ECU Health, we designed the outreach program and cover the cost of this work with those realities in-mind. If we are going to solve the infant mortality issues that our region faces, we are going to have to work together with health care partners across the East. I’m proud to say we are leading the way in that regard and the work is truly making a difference.”

Innovations to bridge gaps

It is no secret that eastern North Carolina is a vast rural region with long travel times between communities. An innovative program launched in 2020 at East Carolina University is helping to make women’s telemedicine, telepsychiatry and nutritional support services more accessible.

The MOTHeRs Project was first offered to patients at primary care obstetric clinics in Carteret County and has since expanded to ECU Health and other clinics in counties across the region. Through formalized partnerships with clinics, patients in the practices are cared for by both an ECU specialist and their local physician through a combination of telehealth and face-to-face visits.

Dr. Dwyer and Outer Banks Women’s Care were the third clinic in the ECU Health system to join the MOTHeRs Project. Maternal-fetal medicine and behavioral health care offerings for expectant mothers has been a much needed addition to the practice.

“We have identified access to mental health care as the greatest need in our rural communities. This need is increased during pregnancy and the post-partum period. Providing this service is a huge addition to maternal health care,” Dr. Dwyer said. “We have already begun to have mental health appointments in our office through the MOTHeRs Project. The feedback from our patients have all been very positive. This is just the beginning of learning how to give the needed specialized care in rural offices.”

Through its ongoing work, the MOTHeRS Project expects not only to provide care to those who need it, but also to generate new knowledge regarding how barriers to care can be better addressed. It aims to be a national model to ensure that every woman in rural America has a safe and healthy pregnancy and delivery.

“ECU Health, Brody and East Carolina University are truly pioneering high-quality rural obstetrics and women’s care services,” said Dr. Michael Waldrum, ECU Health CEO and dean of Brody. “Our hospitals and clinics provide excellent care in communities across eastern North Carolina. The perinatal outreach team trains other smaller hospitals on emergency care, best practices and more. Telemedicine innovations like the MOTHeRs Project makes patient-centered care more accessible. I’m proud of the work that all team members do to help our mothers, babies and communities thrive.”

Resources

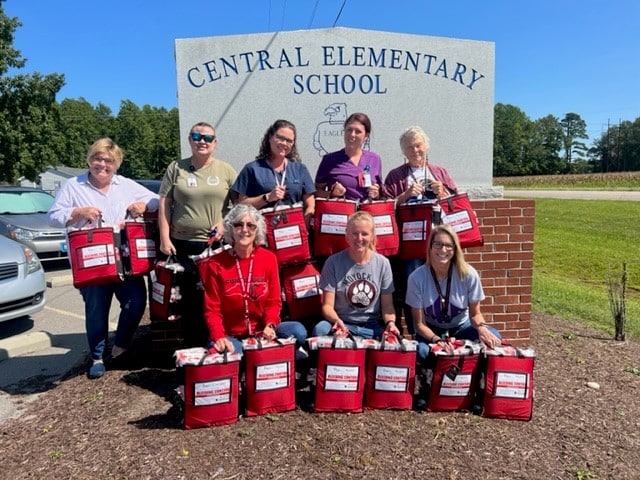

Greenville, N.C. – ECU Health donated Stop the Bleed Kits to public schools in Tyrrell, Currituck, Northampton and Halifax counties as part of its goal to distribute these life-saving resources to public schools across eastern North Carolina. These kits provide resources such as tourniquets, trauma dressing, compressed gauze, gloves and training for school staff in the case of a bleeding emergency before professional help arrives.

“ECU Health is excited to continue expanding our distribution of Stop the Bleed Kits in the counties we serve in eastern North Carolina,” said Erika Greene, pediatric trauma program manager for Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center. “Time is of the essence for traumatic injuries, and early intervention can save lives. In rural areas like eastern North Carolina where the distance between schools and hospitals may be greater, these kits enable school staff to treat children early, improving chances of better outcomes.”

Stop the Bleed Kits are funded by Children’s Miracle Network with training provided by Maynard Children’s Hospital. ECU Health has donated more than 64 Stop the Bleed Kits to schools this year, with a total of 354 kits in 12 counties since the program started in eastern North Carolina. School nurses in each county help train staff to use the kits, which ensures more children can be treated with supplies that do not expire.

“We are thankful for the generous gift of Stop the Bleed Kits provided by Maynard Children’s Hospital for every school in Currituck County,” said Jennifer Solley, school nurse, Currituck County Schools. “An emergency in the school setting can occur at any moment. Stop the Bleed training and equipment in each school will equip the staff with the knowledge and tools needed to respond to any bleeding emergency. With these kits, we are prepared and able to reduce or eliminate the loss of life due to an emergent bleeding situation whether it be a single playground injury or a mass injury situation.”

Preventable blood loss is one of the most common contributing factors in trauma-related deaths. Approximately 40 percent of trauma-related deaths worldwide can be attributed to bleeding or its consequence. If bleeding is managed early, the chances of recovery and survival are much greater. The items in the kits help control the loss of blood, leading to positive outcomes for those who sustain injuries.

Pediatric patients at the James and Connie Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center got a little taste of Halloween as they had the chance to dress up and see ECU Health team members and community groups participate in a parade.

During the parade, floats with team members dress up as everything from Disney’s Up characters to safari themes poured by while patients and families had an opportunity to step outside of their rooms and enjoy some fresh air on a warm afternoon.

Quionna Lofton, the mother of pediatric patient Emoni Salvant, said it was a great experience for her and her daughter.

“It makes me feel really good,” Lofton said. “I didn’t think she would get to experience Halloween today because we are here. This is very nice and well thought out, it was just very lovely.”

Emoni said her favorite float was the Trolls characters and her mother agreed, since she got to see her daughter’s smile light up as it came by.

Various community partners came out to bring a little joy to the youngest patients at ECU Health Medical Center. The Greenville Fire Department brought two trucks to the parade while the Pitt County Sherriff’s Office showed off a safari-themed float. The Down East Wood Ducks baseball team mascot, DEWD, gave patients a big wave from the back of a Jeep while ECU’s mascot, PeeDee the Pirate, interacted with patients and families.

Karolyn Martin, Miss North Carolina 2022, was on hand for the parade as well. She said it was a great experience, and a personally meaningful cause for her.

“My younger sister actually has Crohn’s Disease,” Martin said. “When she was diagnosed, she was in a hospital for about eight months of her year in 8th grade. I know how important it is for families to have people come that care about their children and also to celebrate the people that are making sure children are safe and healthy – that’s so important and why I was so excited to be here.”

Patients had the opportunity to select a costume from those available in the Maynard Children’s Hospital and got to select a party favor, including books and other fun activities.

Chloe Williams, a Child Life intern who helped organize the event, said it was special to see the smiles on the faces of patients and families after the time spent planning.

“I think it’s great. I think it provides a sense of normalization to the hospital experience, because a lot of the time they don’t get to have a Halloween if they’re here,” Williams said. “Just to provide something that they can enjoy and the parents can enjoy, too, is a really special thing.”

Williams said it’s also something team members look forward to each year. Whether they are dressing up and riding along on a float or out in the sea of children, it’s a welcomed opportunity to see patients in their natural setting – enjoying time as a kid.

Jamysen Howard during her NICU stay in 2010.

From premature babies to complex conditions, the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at James and Connie Maynard Children’s Hospital sees the youngest patients at ECU Health Medical Center and provides high-quality, compassionate care while looking after families throughout their NICU journey.

Along the way, many families find a community and support system around them as they navigate the experience.

Thriving 12 years later

Tonya Howard found out at her 11-week ultrasound that her daughter would be born with her intestines outside of her body, a condition called gastroschisis.

While baby Jamysen grew, plans were lining up to have a pediatric surgeon join the team at Maynard Children’s Hospital at ECU Health Medical Center just in time for Jamysen’s arrival. However, when she came four weeks early, the pediatric surgeon received emergency privileges and successfully operated on her just after her birth.

Tonya said the supportive care team helped her and her family immensely during their time in the NICU. While they took care of Jamysen, they also kept the family up-to-date and informed.

“The NICU nurses who, probably about four or five of them I still talk to, kept me up with Jamysen’s progress,” Tonya said. “I had two other children at home, so I’d go home and spend the night and when I’d get up in the morning, the first thing I’d do is call the NICU to see how she did that night. The nurses were the ones that took care of her and they were with her all night.”

Jamysen is now in 7th grade, excels in school and plays volleyball for her school and travel teams.

She also said the NICU community is very strong and has been happy to serve as a support to other NICU families, including one that experienced gastroschisis, just like Jamysen.

Today, Jamysen is 12 years old and thriving. Tonya said while they were told there was possibility Jamysen could experience trouble with physical and mental development, she is now an honor roll student and plays volleyball with school and travel teams.

“We’ve always told her that she can do anything she wanted to do,” Tonya said. “I was like, ‘before you were one day old, you’d already been through a five-hour surgery so you know what, you can do anything you want to do.’ And she’s done just that. She knows she’s tough, she’s never had much fear and she’s headfirst into everything and always has been.”

Jamysen frequently participates in Children’s Miracle Network events as well.

Tonya has a unique perspective on the Maynard Children’s Hospital as a former team member in the pediatrics department, including time before the Children’s Hospital was built.

“At one point the NICU was just one big room. When Jamysen was born, the NICU was what it is now and each baby had their own individual room,” Tonya said. “Everything from the beds to the Child Life

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria.

and now they’ve progressed to where the parents can even log on and see their babies when they’re not able to be there. We didn’t have that while we were there but that’s just amazing.”Rallying around Waylon

Waylon Denny is shown in a crib after having a tracheostomy.

On July 23, 2016, Waylon Denny was born at 23 weeks, weighing 1 pound, 4 ounces. He spent the first 298 days of his life at the Maynard Children’s Hospital, beginning with about four months in the NICU.

Following a surgery for young Waylon, he became sick and needed immediate intervention. His providers knew one treatment, called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), could be lifesaving.

“I mean, they all really rallied right around us,” Waylon’s mother, Sara, said. “They got the doctors and everybody in the PICU that had anything to do with ECMO to come down to look at him to see if he would be a candidate for ECMO. And I truly believe if it was not for his respiratory therapists and nurses fighting for him that day I really do not believe that he would even be here.”

ECMO is a treatment where blood is pumped out of your body and into a machine that removes carbon dioxide and then flows blood back to tissues in the body. One of the providers fighting for Waylon was Dr. Shannon Longshore.

“I remember Dr. Longshore telling us that in a baby his size, 23 weeks, he was already swollen,” Sara said. “Everything he had been through, she should not have been able to get the [tubes] in his neck. And I remember her telling us that she looked at the team in that room and told them that she was going to keep trying because we were two weeks away from going home. And she closed her eyes and told God if it was his will or for him to live, they would go in. Well, those [tubes] went in.”

Waylon started kindergarten this year.

Sara was a first time mom and said it was hard to know what questions to even ask. Luckily, she said, the doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists were there to help. They explained things to her and the family and checked on them frequently.

Six years later, the check-ins have not stopped, she said.

“We’ve had so many nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists, physical therapists and occupational therapists friend us on Facebook just so they can keep following him and see how he’s doing,” Sara said. “And then when we were able to go to the hospital before COVID, and we would go and visit the NICU and the PICU and everywhere where he had been.”

Waylon is six and starting kindergarten and has met every challenge he’s faced in his young life head-on.

September is NICU Awareness Month and Sara said that she and Waylon have NICU Awareness Day (Sept. 30) t-shirts that they wear each year and she’s looking forward to celebrating and recognizing the day once again with her miracle son.

Twins fight through NICU together

Twins Molly and Lucy Davis are shown during their NICU stay.

Owen and her husband Garrett Davis were expecting twins and enjoying a family vacation before welcoming the new additions to their family. But their vacation was cut short when Owen could feel something was not right and she went into labor at 22 weeks.

Molly and Lucy Davis came into the world each weighing just 1 pound, 9 ounces and were immediately placed in the NICU at Maynard Children’s Hospital. The twins were both fighting infections early on in their lives and experienced many tests, treatments, procedures and exams over their 128 days in the NICU.

Owen said they experienced the full range of the NICU rollercoaster during their stay, but they were comforted along the way by the supportive and caring team at the hospital.

“One of the biggest things that I remember were the nurses and our neonatologists,” Owen said. “We still keep in touch with them really on a daily basis. Some of our nurses babysit for us, which is really special. Just the people that we encountered throughout our long stay made it bearable.”

Along with the great support of care teams, Owen said some of her family’s closest friends came from their time in the NICU. She said it is a special bond and shared experience for families of NICU children.

Recently, Owen had someone reach out to her on social media saying their friend was about to have a child at 23 weeks and the two got in touch with each other.

The Davis family takes a photo at the beach.

“It’s really cool to have that connection and to be able to provide insight and support to other families going through what we’ve been through,” Owen said. “So I’ve been in touch with basically a stranger from across the country who saw our story and reached out for some guidance and just a listening ear to be able to bounce questions off of and support and vent. It’s hard to understand unless you’ve been through it.”

Being open with her family’s story has brought comfort to others and she’s happy that her twin daughters are beginning to understand their own story as well.

She said it’s important to her that Molly and Lucy know how strong they are and that their parents advocated and fought for them from the time they were born.

“It was super hard and trying, but it’s also their testimony and they understand that at 3 years old. It’s really two miracles that we were able to witness,” Owen said. “They know, as much as a 3-year-old can. We have their blessing beads, these little beads that they got for every procedure and every test they had, we have them hanging up on their beds and we have their first diapers that are about the size of a credit card. We keep two of those on our entryway table in our living room as a constant reminder of what they’ve been through.”

Owen said she has a video that she put together of her daughters’ NICU stay that shows up in her memories each September and serves as a reminder of the importance of the month for her family — and so many others.